Hally won turf to keep home fires burning

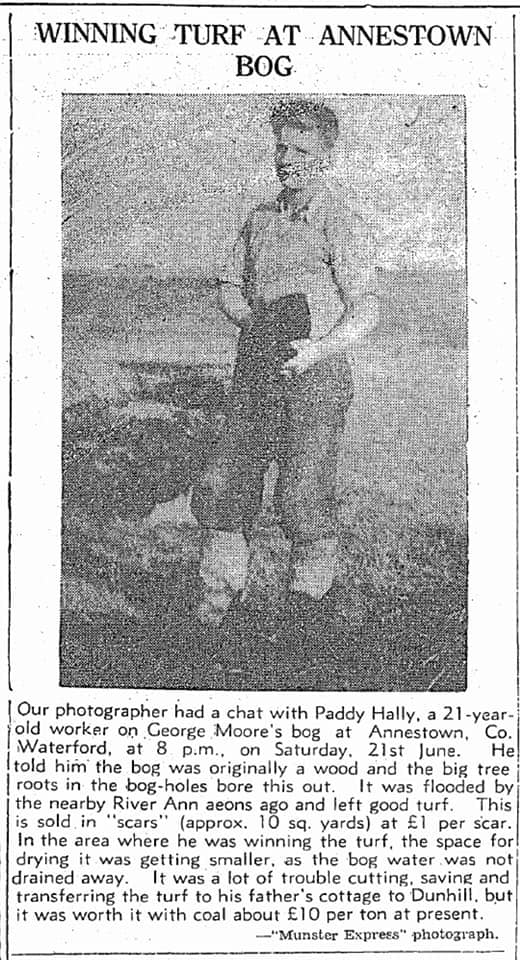

For the times that are in it, a picture of the late Paddy Hally — popular resident of Tallyhoe, Dunhill and friend of a wide circle — winning turf on George Moore’s farm at Annestown Bog on the longest day of the year in 1958.

Paddy explained what was originally woodland had been flooded by the Anne River many moons ago and left good peat. The turf was sold in “scars” (approx. 10 square yards) for £1 a scar. In those years, the annual turf cutting campaign at Annestown would begin in May and the fossil fruits of those labours would be dried come June (the 21st, in this case).

Paddy was cutting it to keep the home fires burning at his father’s cottage in Dunhill come the winter. It was worth the hardship, what with coal costing £10 per ton at the time.

When the “extraordinarily deep” sixty-acre turf bog was discovered below the Castle in the late spring of 1941, a hundred men were swiftly put to work there. Coal imports for domestic use had fallen drastically due to WWII, so a County Council scheme was established whereby each local authority took responsibility for the production of turf.

Waterford Co. Council squads took a lot of fuel from Annestown, as did Messrs. Morris and Spencer, local coal merchants (principally Joe Spencer in Tramore), who acquired sizable allotments and employed 30 men for the purpose of extracting it. The Parish Council also got a share.

The high-quality turf was available just six inches below the surface and the best of it extended over 10 feet down. So close to the city, the discovery, though hampered by drainage issues, saved a fortune on imports. It was one of the very few places in East Waterford where turf could be harvested. Specially modified lorries were deployed to transport it to suppliers in Tramore, Waterford city, and environs.

As of 1944, council turf workers in the valley (many of whom were also Local Defence Forces personnel) were paid 42 shillings for a 48hr week, plus a bit extra for overtime into the night. There were complaints that normal tea rations were denied to those men who wouldn’t work on and that they were forced to drink all sorts of “concoctions” to keep going. (It wasn’t just the turf that needed curing.)

The local authorities programme produced 3 million tons of turf up to its cessation in 1947. The Minister with responsibility for turf development, C.S. “Todd” Andrews (who later ripped up many of the country’s railways, including the Waterford-Tramore line in the early sixties) claimed that “as a result of these schemes, no-one died of cold … or had to eat uncooked food” during the war.

Certainly “the despised fuel of yesterday”, as an Irish Assurance Co. advert called it, had taken on “vital importance” and kept many Irish people alive during the Emergency.

Paddy was aged two when the crisis measures began and 10 when rationing finally ended. They gladly burned a few briquettes in Ballynageeragh and beyond and, war and all, the world kept turning.

Post Comment