Banks of Suir a lime kiln hotbed

Lime kilns (or limekilns) were once common features of rural landscapes throughout Ireland in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Now, most have been destroyed or are faded into the overgrowth. These were structures in which limestone was heated to a high temperature to produce quicklime powder. It was used for fertiliser and the whitewashing of thatched cottages.

The kilns along the banks of the Suir near Kilmeaden are reasonably well preserved and can be seen from the Waterford Suir Valley Railway (main photo). The kilns were sited close to water, as the limestone was generally ferried along the river.

The lime was quarried from Grannagh in South Kilkenny and from there it would be transported on Lighters. Using long poles to push the flat-bottomed craft, a three-man crew would do all the extremely heavy lifting and were paid by the ton load.

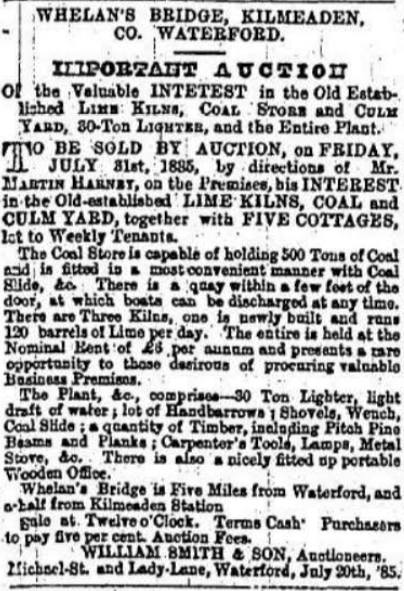

In the summer of 1885, a year after the GAA was founded, an important auction took place at Whelan’s Bridge, Kilmeaden to dispose of the valuable interest in the old established lime kilns, coal store (capable of holding 500 tons), culm yard, and entire plant, including a “nicely fitted-up portable wooden office”.

A 30-ton lighter came with the land. There was a quay within a few feet of the door, at which boats could be discharged at any time. Of the three kilns vendor Hartin Harney had there, one was newly built and ran 120 barrels of lime per day.

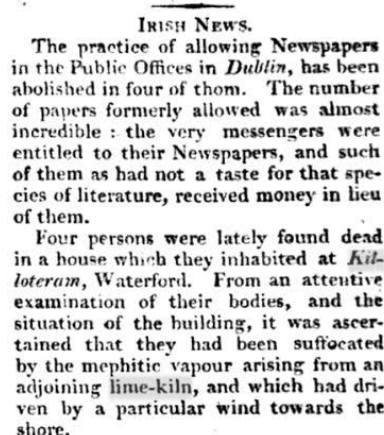

As well as the business premises, five cottages let to weekly tenants were also put up for sale. Living close to the kilns could be hazardous. In 1810, The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle reported how four people were recently found dead in a house they inhabited at Killoteran.

“From an attentive examination of their bodies, and the situation of the building, it was ascertained that they had been suffocated by the mephitic vapour arising from an adjoining lime-kiln and which had been driven by a particular wind towards the shore.”

In a mid-eighties piece for a local history book, Josie Stephenson wrote how Whelan’s Bridge was a hive of industry back in 1850. Edmond Phelan had a house, offices, and shops. James Phelan had four lime kilns and a coal yard. John Byrne had three lime kilns and a coal yard on the Woodhouse side of the bridge.

Small boats came up the river to trade in the area. According to the Grand Jury map of 1818, Whelan’s Bridge also had a paper mill in the old days. At Woodhouse, Phil Power, known as Phil the Miller, had a large mill, office, and lime kiln.

Indeed, in 1856, when they were mapping out the route of the new railway line, one advantage of the chosen course was its adjacency to the extensive lime kilns at Whelan’s Bridge and Killoteran. Lime could easily be taken by freight train from there, to the cost-efficient benefit of farmers along the way, the planners said.

In late 1862, the Farmers’ Gazette referenced the four lime kilns operated by the Mount Congreve estate, which had established handy access points on the Suir.

These were “kept constantly at work during summer, one of them being generally working all the year round, not so much as a matter of profit, as for the purpose of affording employment and of supplying Mr [John] Congreve’s tenants and others in the neighbourhood with lime at moderate rates.

“The limestone is brought from Mr Congreve’s property on the county Kilkenny side of the Suir, as there is no limestone on the county of Waterford side, and the navigable capabilities of that river enables vessels to discharge their cargoes of culm just at the kilns, thereby effecting a considerable saving in point of carriage.

“One way or other, a considerable number of people are employed by Mr Congreve in connection with his lime works, besides being of great service to the neighbourhood,” the newsletter noted.

However, the industry didn’t last. In March 1899, less than a decade and a half after Martin Harney sold up, an article about the union-crippled state of the Irish economy in the Dublin Weekly Nation, headlined ‘A Tale of Ruin’ (and quoting Parish Priest Fr Thomas Hearn) recorded the kilns’ demise.

It told how, at their peak, “the famous Whelan Bridge lime kilns” supplied lime to farmers fully ten miles distant and gave employment to 20 men at least. They often had to get as many as eight boats to bring all the stone from Granny, five miles downstream.

But by the eve of the 20th century these kilns were “all silent and nearly all tumbled down. Everything good materially gone. Is it not well that even incorruptible well-paid politicians yet remain?” the writer asked. Was it ever thus?

Post Comment