Oldcourt newcomers, The Studderts

Having arrived as wartime outsiders, two English sisters fondly remember their time in Killotteran, County Waterford

STRANGERS seeking stability and the safety of neutral territory, the Studderts came to leafy Oldcourt manor in County Waterford during the Second World War. Having been keen to escape the bombs raining down on England, they were equally desperate to fit in with the Kilmeaden/Butlerstown area’s small but established Anglo-Irish Protestant population.

Lieutenant Commander Maurice Eyre Persse Studdert of the Royal Navy grew up as the son of farmers and land agents near the Burren in County Clare; his ancestors having once owned Bunratty Castle. He was privately-schooled in England and entered the Naval Engineering College close to Plymouth, graduating with flying colours. A technical genius, whose groundbreaking work won numerous awards, his career would be short but stellar.

His wife was a red-haired woman some ten years his senior, namely Australian-born Helen Crawford. She’d been sent to her late father’s homeland when she was five, living with her grandmother in Dublin until she died, before being summoned to return Down Under.

Deeply unhappy, Helen somehow fled back to Ireland on her own during World War One, aged just 16. Overcoming the wrench of leaving her brother behind, she enrolled in the poultry keeping course at the Munster Dairy Institute in Cork and later did a diploma in agriculture at Reading University; becoming only the second female poultry inspector at the British Ministry of Agriculture.

It was around this time that Helen met Maurice — more commonly known as Michael — a dashing naval officer stationed in Malta, where they were married in late 1933. A daughter, Elizabeth, was born there two years later and christened on board the ‘HMS Revenge’.

Her two sisters Helen and Caroline, both born in England, completed the family in 1936 and 1941 respectively. The sisters called each other “E”, “B” and “C” for short, and still do to this day; though Helen was more often called Belinda to differentiate her from her mum.

When WWII broke out, Michael was initially posted to the Far East but was soon retained at home in the Ordnance Department. His fluency in Russian and German meant he was also used to interrogate POWs; something he hated. Among other notable accomplishments, he is recognised as instrumental in inventing the revolutionary Wrayflex, forerunner to the modern camera.

At the start of the forties the Studderts moved to the Somerset coast but in the autumn of 1943, anticipating the V-bombing of UK cities and wanting his family out of harm’s way — and particularly away from the Admirality base of Bath where they lived — Michael bought a secluded property across the Irish Sea in east Waterford.

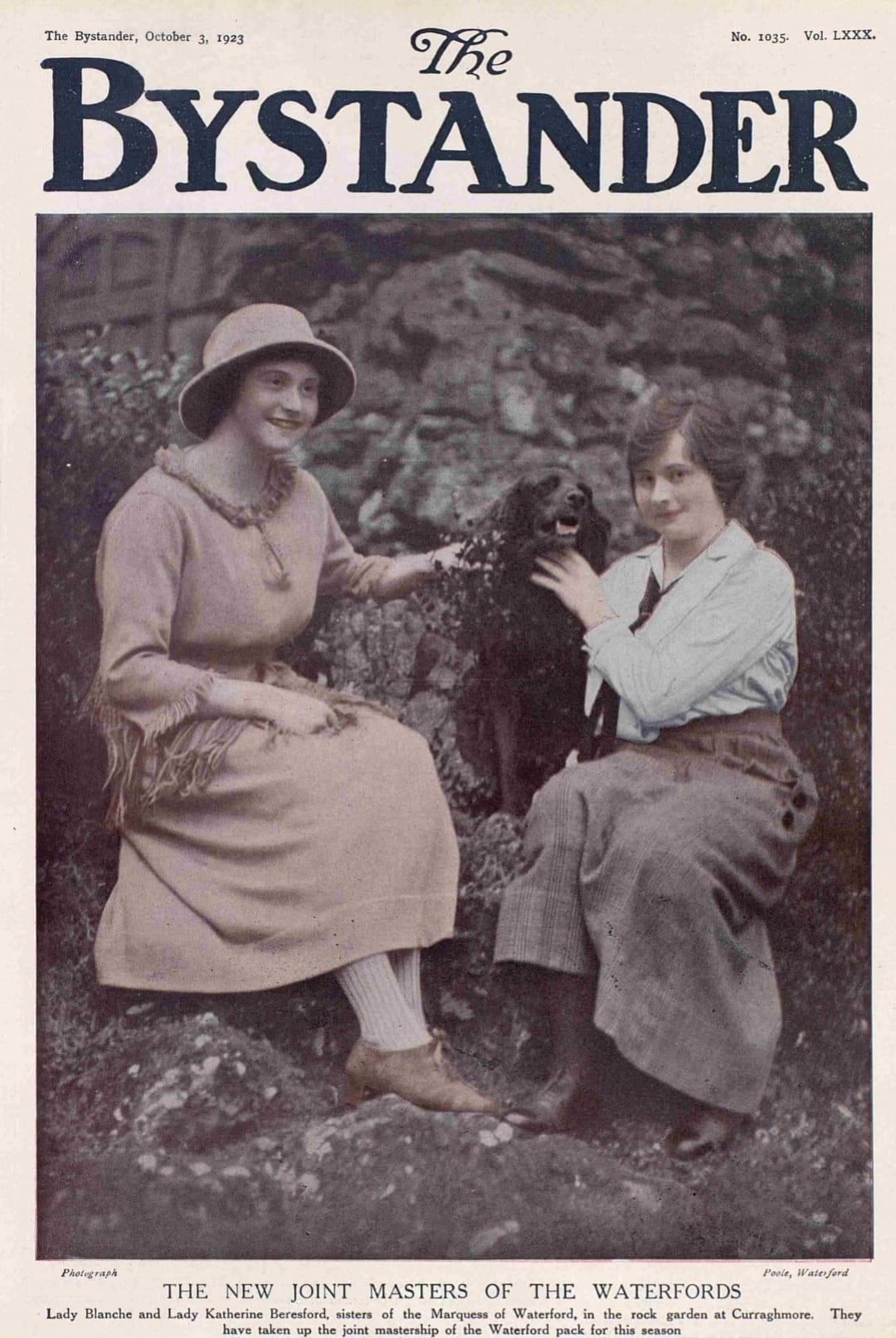

Oldcourt had long been the home of the Millers, having been built in 1730 as the Protestant Bishop’s residence. Eldest son of the late Bishop of Cashel and Waterford (who was the last Bishop to live there, and bought it from the Church of Ireland), Lynden Roberts Miller took possession of the house and changed its name from Woodstone to Oldcourt, having married Lady Patricia Beresford from Curraghmore.

Youngest sister of Lord Waterford (and Lady Katharine Dawnay of Whitfield Court), she was given Georgestown House by her brother around that time and so they moved from Oldcourt to Kill. As things would turn out, the mother of Elizabeth Studdert’s second husband, David, was none other than Patricia Miller.

The oldest wing of the property had been an 18th-century linen school. In the Studderts’ early days in the large, rambling white house near the River Suir, there was neither electricity nor a phone line to tap into. Water was pumped from a tidal stream in the adjacent bog, while the more “delicious” drinking variety came from “a romantic-looking well surrounded by ferns.” The surrounding lands were let for grazing and tillage.

Conscious that they were viewed as “outsiders”, the family employed occasional staff from the locality during their initial spell at Oldcourt, and later one or two in the early sixties when Helen ran it as a guesthouse for a couple of years. “When I was little, Margaret [Cissie] Hayes was virtually a nanny for me, she was great,” recalls Caroline, who later made her living as a writer and journalist.

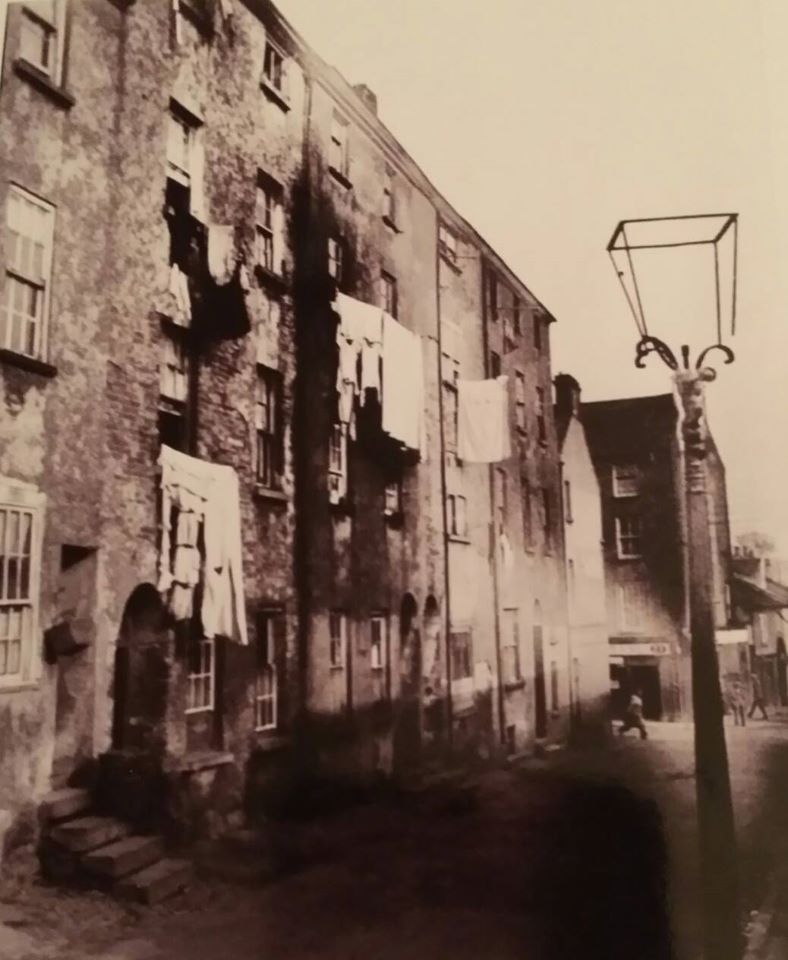

“I’ve put her or her likes in quite a few stories, I can still hear her telling one of her jokes … She had dark hair and blue eyes, proper Celtic colouring, red cheeks, and was quite well built, as they say. My mother was very fond of her too. She lived in London later and worked as a very classy maid; all her employers adored her, and I would get hand-me-downs from them to her and then to me! I saw quite a bit of her when I was living there in 1964-5. Later in life, she [Cissie] lost weight – I took my kids to meet her when they were I think about 14 and seven; she was living in Waterford in the little street by Reginald’s Tower. Later she moved somewhere near the Comeragh mountains but sadly I didn’t hear when she died; otherwise I would have come over from whatever country I was in.”

Caroline recalls “another redhead, Teresa, who was great fun and we got on well. Later she got married and moved to London and I stayed with them there for a bit. We lost touch after I went back to Ireland and then abroad.”

The three Studdert girls were mostly home-schooled, apart from one term in Newtown. Their Quaker education was short-lived as, with no petrol to be had, the five-mile trip back and forth twice a day by trap was too much for their pony, ‘Togo’, which had previously pulled a greengrocer’s cart before they bought him in Bath.

Elizabeth demonstrated an early and clearly-gifted interest in modelling and sculpting and from a young age she made little figures as gifts. However, her evident talent was stymied by not alone a lack of tools and raw materials but the active discouragement of her parents, who wanted her to pursue a more viable career.

After the war the siblings’ already overworked father, frequently assigned to top-secret missions, was pressurised to came out of hospital to take up an appointment as head of the one-man British Naval Gunnery Mission in Europe, with sole responsibility for researching and adapting German scientific development. And so in 1946 he, his wife and children went to live in Minden (which had been a hotbed of German science before being bombed to bits by the Allies) for a couple of years. Elizabeth learned under a German sculptor, while her mother gave English classes.

Once, when still unable to speak after a successful tracheotomy, she wound up the phone and rang a bell into it. Mrs Sheehan, the operator of the Kilmeaden exchange, had her son drive the 3 miles to check what was up with Mrs Studdert.

Having moved back to Oldcourt in 1948, Elizabeth and Helen were sent to boarding school in Surrey. Their father was increasingly unwell and their mother got throat cancer. Once, when still unable to speak after a successful tracheotomy, she wound up the phone and rang a bell into it. Mrs Sheehan, the operator of the Kilmeaden exchange, had her son drive the 3 miles to check what was up with Mrs Studdert.

Indeed, Elizabeth recalled how Mrs Sheehan, “an excellent woman”, could sometimes tell the caller where a person was when she tried to connect and they were not at home. “’Not that I was listening, mind you,’” she’d stress.

After Michael sadly died in a Dublin nursing home just shy of his 41st birthday on St Patrick’s Day 1951, his wife — who was left with a large country house and three daughters but relatively little money — got to know many of the locals around Killotteran a lot more. Elizabeth remembers how their neighbours’ innate sympathy shone through and “kind Willie Power” came to help tend Mrs Studdert’s large garden in the evenings after doing his day job as head gardener at Mount Congreve.

Caroline also recalls: “Willie and Nellie Power lived in the cottage opposite Killotteran church and I have childhood memories of hearing him and my mother talking for hours, the leisurely rising and falling of their conversation … He looked after father’s grave [at St Peter’s Church, Killotteran] for years, right up to when mother was finally buried beside him, as she wished.”

She can remember staying at Mount Congreve “when my mother was having her throat surgery, I used to go downstairs (sic) and the maids would spoil me rotten with 3 Counties cheese. Once they put me in the little hatch and pulled me up to the dining room. Lady Irene and Major Congreve were very kind to me, and I used to ride over to practise piano, at which I was useless. Everybody went the rounds of these sherry parties where there were the same people, and whenever Major Congreve met Lady Patsy [Miller], he would say, ‘Been killing any more donkeys, Patsy?’ — referring to some ancient incident when she ran into one, but didn’t kill it as far as I know.”

Caroline, who often rode with the Waterford Hounds, had a young pony, ‘Dorcas’, “who was a bit wild, and at one point I would beg various farmers for a ride on their working horses to get more experience. The sweetest was Fitzgerald’s ‘Lily’, a chestnut, and Fitzgerald was a lovely man. The farm was down to the right towards the river near the top of the big hill going down to Mount Congreve; he bred greyhounds and they all had very nice natures.

“Then there were the Daunt family; unusual in that they were Protestant farmers and came to Kilotteran church. Francie Daunt played the dreadful little foot-worked organ. Willie Daunt once sat ‘Dorcas’ out when she had a bucking phase – Dickie Walker, another character, had been schooling her a bit. We didn’t have pony clubs or riding schools then, so it was very do-it-yourself. I went riding once or twice with Bridie O’Mahoney. They lived at the Holy Cross and she later started the riding school near Oldcourt.”

Other neighbours Caroline remembers included “the Maxie Halleys, who lived above us. It was so sad that Rufus died. Walter Halley helped me make jumps for one of my gymkhanas. He was very good-looking, also red-haired. Their mum was a bonny woman. Apparently she nearly died in childbirth one time and Maxie went to Mass every day in thanks for her living. Mr Whelan, who lived in the little lodge at the top of our drive, also went to Mass daily.”

Helen Studdert the elder was a strong advocate of women’s rights and lobbied to get piped water into the cottages in the locality so that they didn’t have to carry buckets for miles. She started the Waterford branch of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association country markets with her friend Vera Cox from England, who visited her a few times a year. Before Helen got married, she and Vera (otherwise known as PT) had run a small farm together near Portsmouth in Hampshire after the Great War, but gave it up when the slump came in the twenties.

Elizabeth’s mother recommended that her eldest daughter study languages at university in Scotland, while her two sisters went to Trinity; Helen heading to Dublin five years before Caroline, and both went to live in England after graduating. It was while attending St Andrews in Fife that Elizabeth met Nigel Dyckhoff, a red-haired Northern Irish Catholic. Her determination to marry him caused ructions at home. Her mother was “anti-Roman”, even though a drawer full of Rosary beads would be found in her bedroom years later. (It’s thought they may have been given to her by the nuns in the Good Shepherd Laundry, where she sent sheets to be washed after Oldcourt was turned into a guesthouse, and was probably too polite to refuse them.)

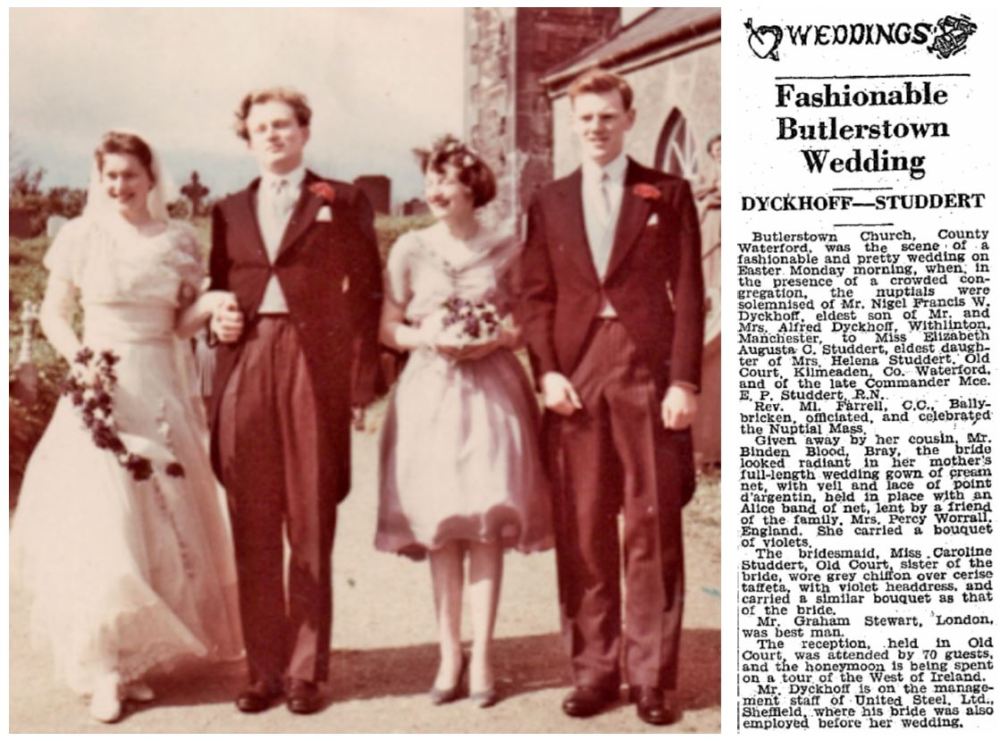

Mrs Studdert’s attempts to scupper the wedding — sending her daughter to various sages, including the Church of Ireland Bishop, in an attempt to persuade her to renege — failed and the couple exchanged vows in Butlerstown on 30th March 1959 (below). A cousin, Dennis Pringle, a High Court judge, gave Elizabeth away, and her sister Caroline was bridesmaid. A Scottish friend from college was best man. The newly-weds began married life in a flat in Sheffield, where Nigel worked for United Steel, as Elizabeth had too before their marriage. Their sons Andrew and Martin soon followed.

In 1960 Elizabeth’s sister Helen married Christopher Pearson from Norfolk in the tiny grey church across the bog below Oldcourt, where the receptions for both weddings were held. The following year it was marketed as a country house, which Mrs Studdert advertised in the Irish Times as a peaceful rural getaway with “good fires, plenty of books” and “space and adventure for children”. She carried on the farm at Oldcourt for 13 years after her husband died, growing prize vegetables and involving herself with the ICA.

Indeed, as a schoolgirl Elizabeth remembered hacking away at the “jungle” below their home and, to the astonishment of the Waterford agricultural adviser, planting Sitka Spruce in the bog. He told her to screen it off with Redwood instead. In truth the spruce looked “pretty pathetic” and never grew above 2-3ft, she admits. But they dried up the ground to the extent that her mother could use the Hayter rotary grasscutter on the area.

Under advice to sell from her bank manager, Mr Stringer, Oldcourt was put on the market and bought in 1964 by Major Donald and Finola Cuthbertson-Smith, who lived there until 1977. Mrs Studdert relocated to Kilranelagh House, near Baltinglass in Wicklow, which was owned by Germans, the Van Westerholts, who only came over a couple of weeks a year. She continued to host ICA guild meetings there.

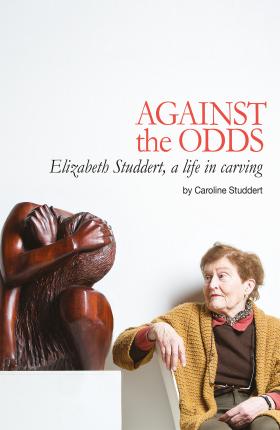

Meanwhile, Elizabeth, who’d taken up teaching after finishing university and occasionally produced sculptures and pottery, went back to college in the mid-seventies when her sons were practically reared and belatedly came into her own as an artist. Her skill with the human form earned her a worldwide following and has been recognised with commissions and exhibitions in London, Paris and Amsterdam. She has wood, stone and bronze sculptures in many local galleries and private collections in England, Wales, Germany and Holland.

She lived and worked mainly in Wales from 1966 to 1984 (the year her mother died) and then in Winchester and Surrey; she and Nigel divorcing in the mid-eighties. She soon met her second husband, retired army man David Miller, Lady Patsy’s son, whom she had known growing up back in Waterford. Caroline writes that her mother would have looked down approvingly on this particular union in 1988; a fateful match which would span the next 25 years, coinciding with a rich vein of creativity on Elizabeth’s part. Though progressively ill, David died suddenly in 2013 and was buried in the chapel at Curraghmore.

Today, when she is not in Scotland, Elizabeth lives near Aylesbury in a small house designed by her son, Martin, who is quoted in the book as saying, “When Elizabeth was young and wanted to sculpt, she said she literally saw the sculpture inside the block as if in a very bright light, and all she had to do was to take away the rest of the block.”

To document Elizabeth’s story of passion and perseverance, and showcase her astonishing body of artwork, Caroline Studdert has authored a beautifully written, designed and illustrated book (below), which was published last spring. She lives in London, where she first moved to in 1964, while Helen resides in Norfolk. All three have led interesting lives since leaving Oldcourt, proud to have grown-up families.

Caroline is happy to hear the sisters’ old home in the Waterford countryside has been revived. “In 1984 when my mother died, it had, I think, been fairly recently bought by a builder, who put up a colonnade (which we thought looked rather odd). The wife was very nice and lent us a bucket to clean up the church for the funeral, and they sent over a wreath. The drawing room looked the same; they had furry wallpaper in the hall and good china. When it became a hotel, I visited it with Margaret [Cissie] and couldn’t make head or tail of where everything had been as they’d changed it completely. I did hear it went under, and it’s nice to know it’s back in business again.”

*Based on adapted extracts from “Against the Odds: Elizabeth Studdert, a life in carving” (published March 2019), together with an interview with the author, Caroline, and other research.

Main photograph: Sculptor and biographer – sisters Elizabeth and Caroline Studdert. (Photo from ‘Against the Odds: Elizabeth Studdert, a life in carving,’ 2019.)

Post Comment