Holy Cross casualty carried cross-country

The last sights, rites and nights of Irish Volunteer Johnny O’Rourke

“There was nothing in the line of stimulants in the shop and the only thing we could get was port wine. We gave John a little of this, and, placing him on the door, we brought him to Butlerstown Castle and tried to get aid.”

D Company colleague, Mick Ryan

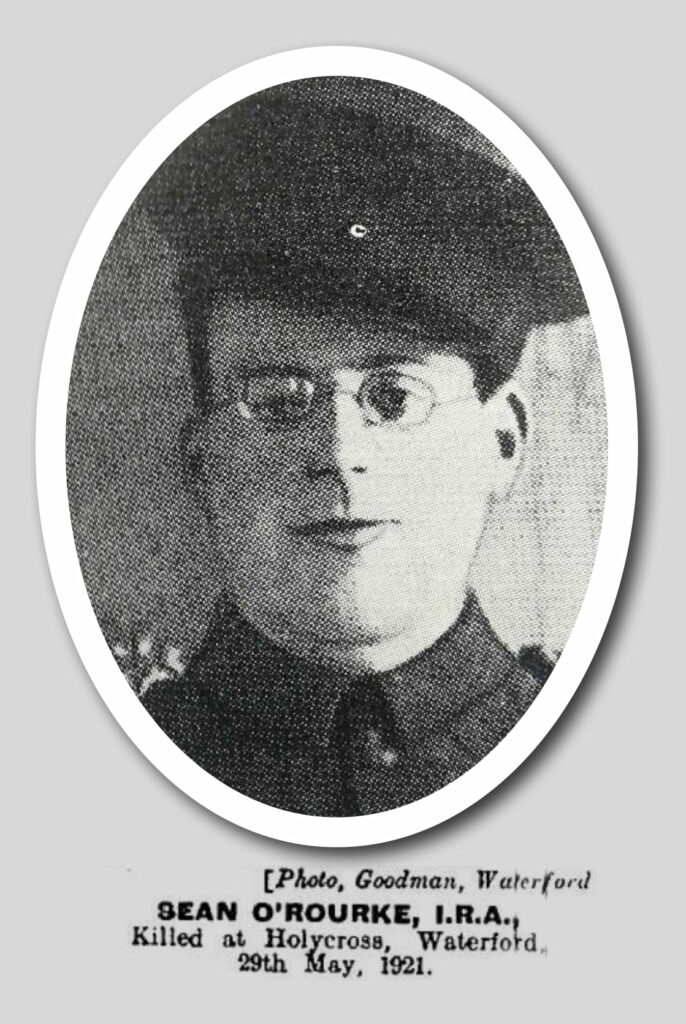

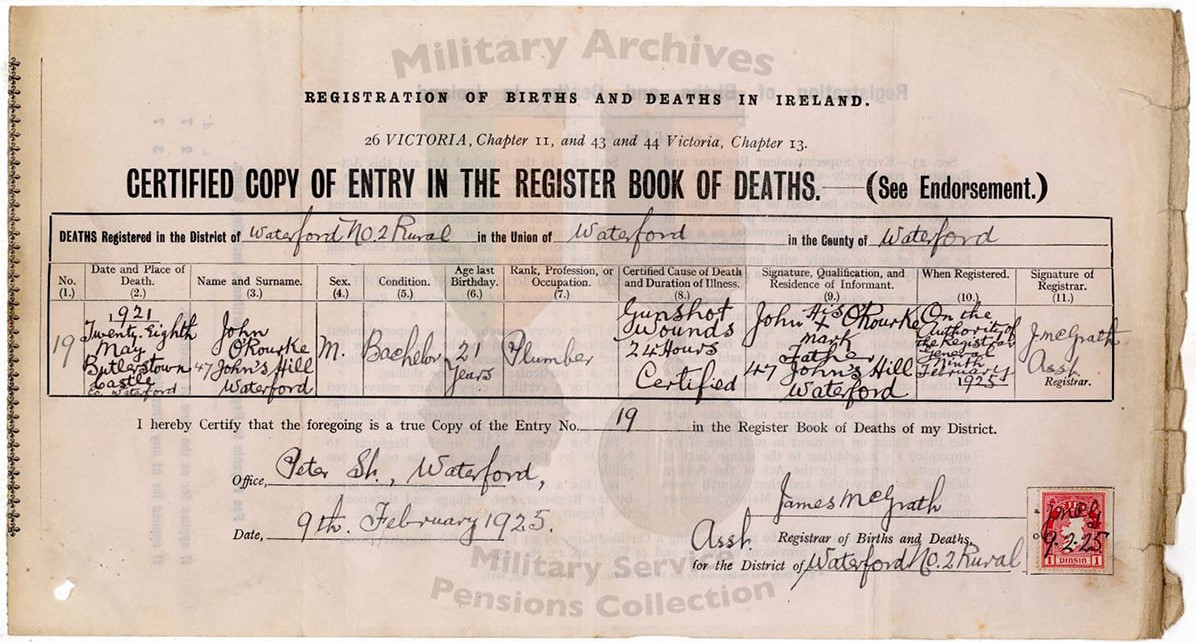

Irish Volunteer Seán O’Rourke was killed in action at Holy Cross, Butlerstown, on May 29th, 1921.

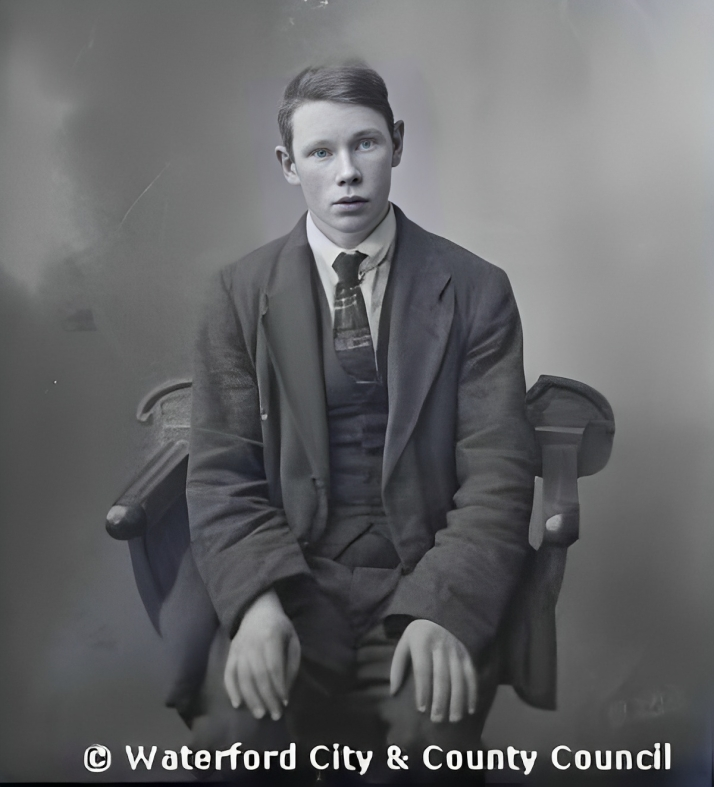

A resident of John’s Hill in the City, the 22-year-old East Waterford Brigade member, who was just out of his apprenticeship as a plumber, had joined the Sinn Féin movement after the Easter Rising.

Entering military service with Óglaigh na hÉireann in 1918, he became what was known as a “contact man” – dispatch carrying, shifting arms and ammunition, and doing various other errands for the Michael Collins-led underground army.

Engaged in the last throes of the War of Independence, the entire City-based D Company 4th Battalion was mobilised for a harassing operation in the Butlerstown-Kilmeaden area on the night of Saturday, May 28th – part of a guerilla strategy to cut off transport routes beyond the borough boundary.

Over a four-mile stretch of countryside, more than a hundred I.R.A. men drawn from the town, Dunhill, Portlaw, Ballyduff, Fenor and surrounding districts proceeded to their assigned posts at 10 o’clock. Every available implement was carried from a nearby arms dump, including crosscut saws, axes, hacks and crow-bars.

They also had gelignite to blow up bridges, including the one at Whitfield; an operation which Volunteer Michael Ryan admitted they made “an unholy mess of”, only succeeding in putting a few holes in the structure. “As it happened this was a blessing in disguise,” said Ryan, learning later that the water main from Knockaderry reservoir to the City was laid over the crossing.

Still, a belt of obstructions was mounted on all routes between the City and Kilmeaden. The Gracedieu road heading down by the Pike at Dooneen to the Sweep was completely sealed up. Trees were felled on the main Cork Road and those arteries branching off it, including along by Mount Congreve.

At the Holy Cross, the 4th Battalion men, who had worked from half-nine in the morning till near midnight chopping down trees (albeit most had fallen the wrong way) were then ordered to knock a wall and put the stones across the road, which, having no picks, they did with their bare hands.

GUNFIRE

Johnny was put on patrol-guard duty at the top of a laneway a few yards on the town side of the former R.I.C. Barracks, which had been burned the year before. His task was to provide warning cover for an entrenching party engaged in digging up a section of the main road so that British army trucks couldn’t get through.

In his 1954 witness testimony to the Bureau of Military History, Waterford volunteer Thomas Cleary of Ballinakill, a member of the same City Batallion, said shortly before the shooting he saw Seán standing at the laneway and bade him “good night”.

Cleary said he told a colleague there and then that whoever had placed Seán on outpost duty at that spot had made an error, explaining: “Seán has a great Irish heart, but his sight is very bad. In fact, he did not know me passing but he knew my voice. How true were those words of mine for we were only gone up the by-road for about 200 yards when shots rang out.”

At around 4 a.m. a British military cycle patrol was held up by the trees felled near the junction. Three officers dismounted, revolvers in hand, to reconnoitre the position. Two were fatefully wearing ‘mufti’ or civilian clothes. They spotted Sean’s outpost. He didn’t recognise they were the enemy until it was too late, mistaking them for colleagues due to their plain dress.

On the first anniversary of the shooting, a Waterford News report said Seán “was approached by three officers, peremptorily commanded to put his hands up and when his captors had taken from him his revolver [a .45 Bulldog Webley volunteers had grabbed from a R.I.C. District Inspector some time previously] he was conveyed down an adjacent laneway and fatally shot.”

(Historian Pat McCarthy wrote many years later that the question of whether Seán’s eyesight was a factor remains “a moot point”.)

Thomas Brennan, Vice-Commandant of the same Company, later corroborated this version of events, testifying that O’Rourke told him how one of the three officers shot him and when he was lying on the ground, the other two fired further bullets into him. Probably thinking he was mortally wounded, they sped back into the city to summon reinforcements, reckoning a major Republican operation was in progress.

STRETCHERED

But by then the I.R.A. had mostly evacuated their main position a couple of hundred yards away. Having heard the blasts, Cleary and others — including Michael Ryan — rushed to Seán’s aid. He had his rosary beads in his hand and was praying. “They got me with five shots. I thought they were some of the boys,” he told them, according to Ryan’s account.

Though bleeding severely from his stomach and barely conscious, Seán asked for and smoked a cigarette. When they asked John what had happened, “he said officers of the ‘Devons’ [Devonshire Regiment] in civvies had shot him,” Ryan added.

Brennan, Ryan and others told how they ripped an outhouse door from its hinges at Pat Reddy’s pub across the road to use as a stretcher. “There was nothing in the line of stimulants in the shop and the only thing we could get was port wine. We gave John a little of this, and, placing him on the door, we brought him to Butlerstown Castle and tried to get aid,” said Ryan.

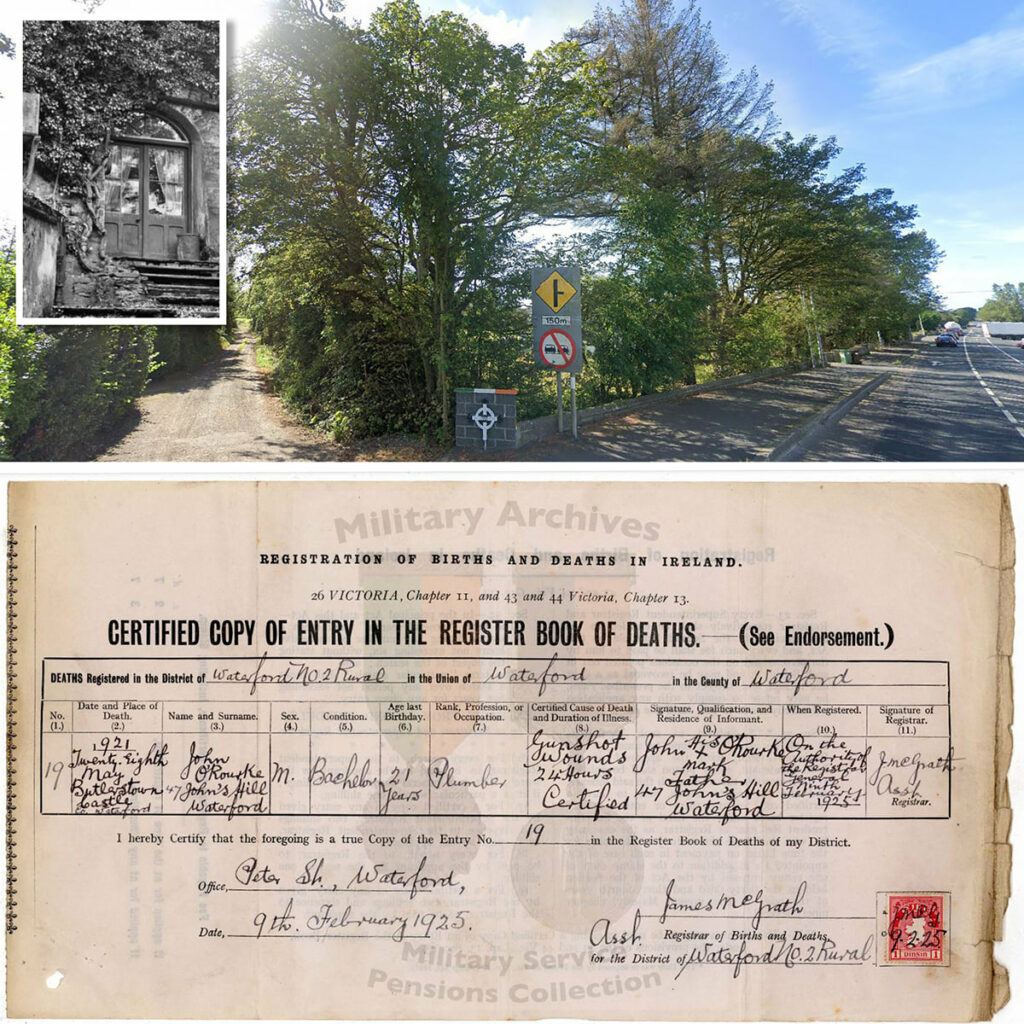

The laneway where he was left for dead ran from the main road through a bog to the castle. Semi-derelict, the former fortress regularly housed I.R.A. drills and would be seized by anti-Treaty rebels during a brief Civil War stand-off with the Free State Army in 1922.

At the time Seán O’Rourke was shot, the Castle’s living quarters were occupied by “sympathiser” Michael O’Connor, a horse dealer who began renting the habitable part of the property from John Nolan of Kilronan in 1917.

Awakened by a knock on the window just after dawn, O’Connor — who wrote an account of the events for the Munster Express in 1934 — got his wife and infant daughter out of their bed and laid Seán down. Realising he was “in bad shape,” Tom Brennan sent two I.R.A. men into town for a priest and doctor.

BLACK AND TANS

Administering the last rites, Fr. Patrick Hackett from John’s College came and went. Having been stopped by troops en route, he pretended to be on his way to Sunday morning Mass in Butlerstown.

Shortly afterwards, two lorry-loads of soldiers and Black and Tans came up the Castle Road from the Cork one. Forcing civilians at gunpoint to help reopen the roads, they had searched nearly every house in the immediate vicinity.

A sergeant in one vehicle knew O’Connor, who’d gone to his gate thinking it was the doctor, and they exchanged salutes. The troops didn’t stop to search the house, in which there were fourteen volunteers having breakfast, but it was clear the danger they were in.

Tom Cleary testified: “The military were out in full force. They searched the whole countryside for Seán O’Rourke. They trailed the blood up halfway the boglane way. They raided the Castle and many farmhouses in the district. They turned all beds out and tried all cowyards, stables, haylofts… They were going around all day but could not find their man, for Seán was in a very safe place.”

Just about hanging on for dear life, O’Rourke was treated by the “always available” Dr Phil Purcell of Parnell Street, who’d also convinced troops he was going to church. He advised the volunteers to remove Seán as soon as possible to somewhere he and his brother Nicholas, a medic in Tramore, could operate on him more safely (the Castle being visible through military field glasses from the Holy Cross). The intended haven was the house of the Fenor curate, Fr Crotty, at Ballycraddock.

With Mrs O’Connor staying at Seán’s bedside, the British military passed the Castle four more times that day, still searching dwellings. Shortly after midnight, with the coast deemed clear by watchmen, I.R.A. members from Dunhill arrived to take their fading colleague the six miles cross-country.

SUCCUMBED

Small in stature but stout, Seán was fixed on a rigged-up stretcher of poles and coats as comfortably as could be and they headed off over the fields. Guided by a small network of intermittent scouts, the four carriers were given respite by relay helpers here and there. All this had been arranged at a Brigade Staff meeting in Fenor that afternoon.

His body more numbed than pained, Seán spoke occasionally and calmly to the men taking his weight as they wended their way through Lisnakill and Pembrokestown. But as they reached Ballymote, he appeared to become fainter and the stretcher was laid down on the ground.

Clipping/photos: Munster Express

As the stretcher-bearers bent over him, O’Rourke asked for a particular I.R.A. officer to whom he was much attached. The individual in question had gone to Tramore to contact Dr Purcell and, to comfort him, Seán was assured he would be back shortly. He then asked for a cigarette. A comrade lit one and held it between Seán’s lips. He puffed at it for a moment, his features suddenly flickered, and death came over him.

The men decided to take his body to the Sacristy of Dunhill Church, still some distance away, and leave it overnight before arranging a burial, which would have to be secret for fear of attracting reprisals upon family, friends and identifying the victim’s acquaintances.

The next morning (Monday) an I.R.A. officer from the Dunhill-Fenor area was deputed to go to Waterford to procure a coffin. A coffin and horse-drawn hearse were booked for a fictional ‘John Power, Annestown’, complete with matching breastplate. The bemused driver was duly held up and relieved of the coffin at Reisk and told to back into town and stay schtum.

The plan remained to bring the body to Dunhill for burial but the British were scouring the area for wanted men and also checking graveyards for freshly dug plots. They’d even combed the cemetery in Dunhill that day; oblivious to the fact Seán O’Rourke’s body was in the church sacristy.

Thinking better of their original intention, a group of I.R.A. men dug a grave at the ancient Reisk Churchyard instead. Later that night the coffin was transferred by ass and cart to Dunhill where, close to midnight, comrades placed the habit on Seán’s body and enclosed his remains.

They were then taken back to Reisk by the same means, with the route lined by scouts. A few kneeling men said a whispered prayer around the graveside and the casket was lowered beneath the soil.

EXHUMED

That autumn, following the Truce, Seán O’Rourke’s remains were exhumed and re-interred in the Republican plot at Ballygunner. This grave would be cared for over many years by David Shanahan of The Clashes, Paulsmills, Butlerstown.

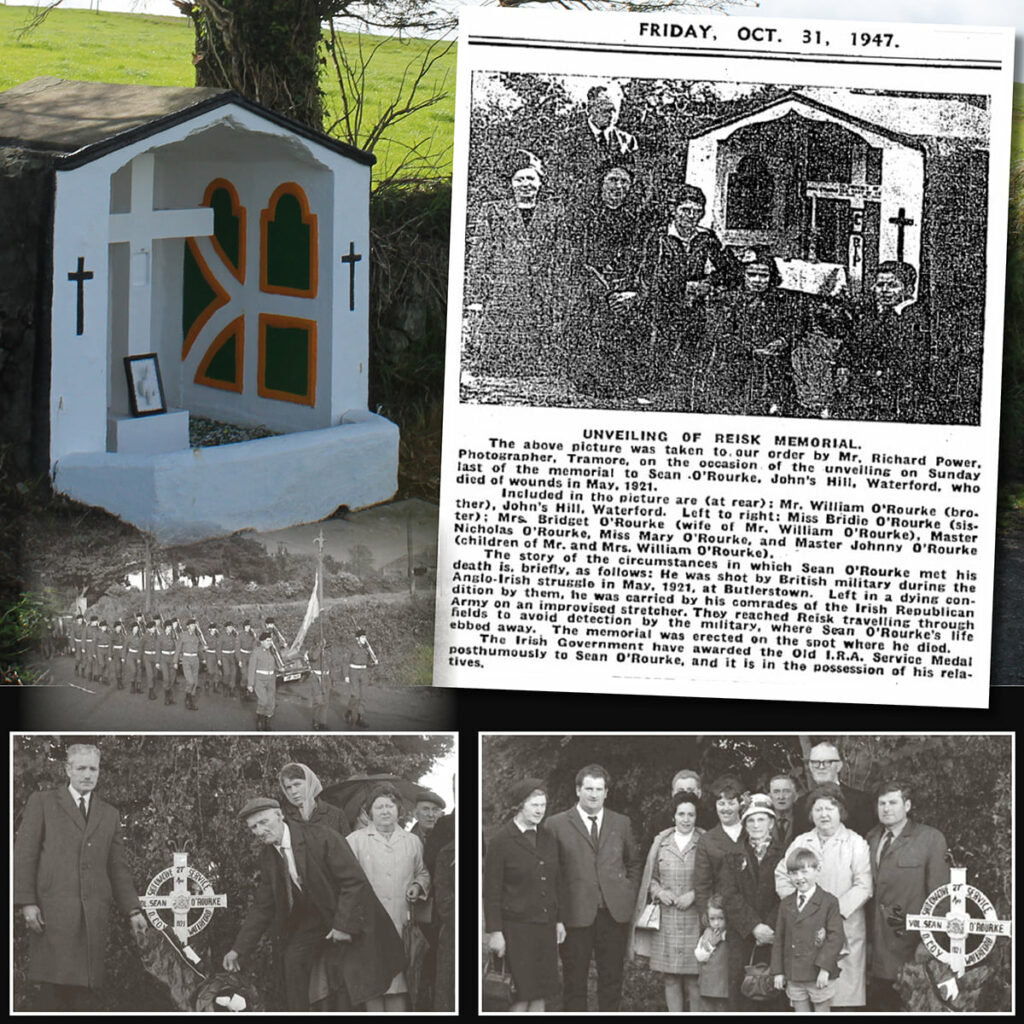

In 1947, with the Dunhill Fife and Drum Band playing the National Anthem and old I.R.A. officer James Power, Ballycraddock, presiding, a memorial was unveiled at the exact spot on the roadside where Seán finally succumbed.

Members of his family were present to hear former Freedom Fighter Nicholas Whittle, who was almost killed in the Pickardstown Ambush in January 1921, recount the events leading up to Seán’s demise.

Noting the efforts of local woman Mrs James Burns and committee in initiating the Reisk Memorial project, he said: “It points out the old lesson that it is not in the great political parties will be found the well-springs of nationality, but in the hearts of the plain people.”

The Last Post and National Anthem filled the air before a challenge hurling match took place between Dunhill and Ferrybank in an adjoining field.

In 1971, on the 50th anniversary of John O’Rourke’s death, an old Republican parade assembled at Ballycashin and proceeded to the Holy Cross. After three volleys were fired, an oration was given by then-GAA President Pádraig Ó Fainnín and the Last Post sounded by trumpeters Frankie King and Tommy McGrath. Two years later a memorial was erected there also. This cross was renovated by Andrew Cusack in 2015.

John O’Rourke was posthumously awarded the Old I.R.A. Service Medal by the Irish Government. Nicholas Whittle wrote in 1946 that Seán, a handy hurler, was a quiet type but had “a sense of humour that would break through in the most adverse circumstances.”

Indeed, Company captain Daniel Ennis, who was overseeing the failed Whitfield bridge blow-up, said he’d seen Johnny on a pony jumping a stone barrier on the road just after midnight and told him to desist and return to his look-out position. The last fence before the last post.

Sourced from www.militaryarchives.ie and various local newspaper reports, as well as Michael O’Connor’s 1934 account courtesy of ‘Unlocking Butlerstown’ (2016).

Post Comment