Tommy’s threshing days ended with Troubles

Dunhill icon O’Brien killed in Pickardstown Ambush

“Death gives us sleep, eternal youth, and immortality.”

— Jean Paul Richter

Remembered in his native Dunhill as a very physically strong young man, Tom O’Brien from Ballycraddock was quiet and reserved but “an open book” to those he trusted. He was said to have been immensely popular with youngsters and went out of his way to help others.

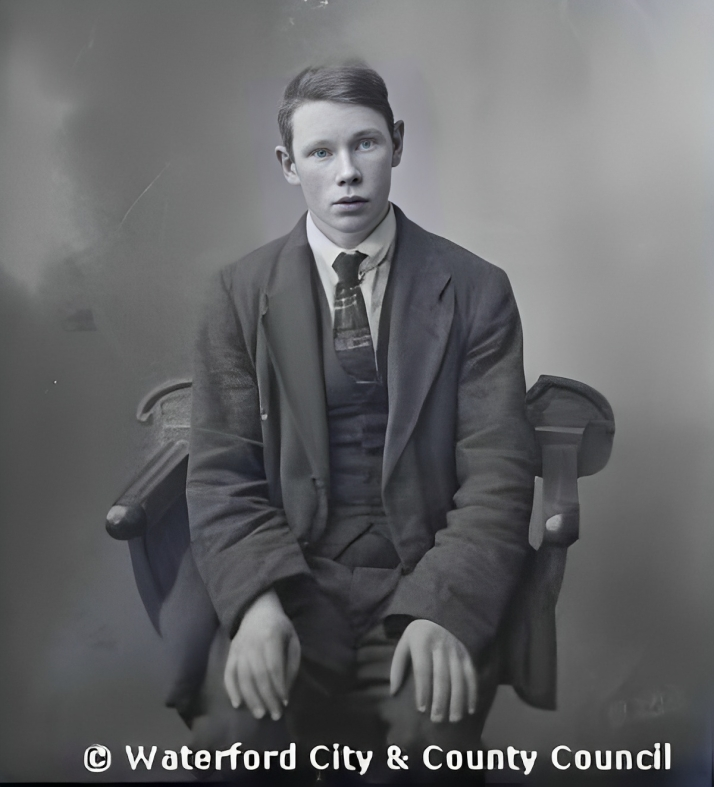

In his mid-twenties when he was killed in the Pickardstown Ambush, a few years earlier he’d been captured on camera, above, hard at work at a parish threshing at my grandmother’s homeplace, namely Powers (The Castle), Carrigadustra, Kilmeaden.

Tommy, as his friends knew him, was born in 1897 and went to Dunhill School, as did his six siblings. His mother died around 1910 and her second-youngest child was never going to be anything other than a farmer, just like his father, Pat.

But with the country in turmoil and his community something of a rebel stronghold, he gravitated towards the Republican Movement and became a familiar figure in Dunhill Sinn Féin club circles.

It was inevitable that he should join the Irish Volunteers, the Republican Brotherhood, and the I.R.A. A mainstay of the local company during the War of Independence, Tom was a member of the party that attacked Kill barracks in 1920 and he had a further brush with British troops that year whilst burning down Annestown R.I.C. Station.

On the Thursday night of January 6th 1921, the eve of his death, Tom and friends attended a céilí dance in the Dunhill Sinn Féin Hall at Killowen.

The following evening he and six other men from Dunhill assembled at McDonalds Creamery, Reisk. They headed across country in the darkness and stopped at the house of Mrs Forristal (née Bridie Cawley), captain of the Tramore Cumann na mBan branch, for their tea.

They promised to call back to her house at Carrigavantry if their mission was successful, namely a planned midnight ambush of a British patrol on the outskirts of Tramore that went badly awry as a result of, it appeared, a premature shot, though the exact circumstances have been hotly disputed since.

A few days later some of the unit returned to collect two wreaths – one for Mikie McGrath, the other for Tom; revisiting the scene of their last supper together.

The findings of the inquest thus described Tom as an unknown. He was interred in the Republican plot at Ballygunner; his burial place recorded as “anonymous”. A military officer was reported to have advanced at the graveside to inspect the coffin to check if it had been inscribed. The breastplate was bare.

“In fact, Tom’s horse and car was always in requisition when his neighbours required goods at the local creamery, and he attended to those duties with a grace which was all his own,” recalled Pickardstown survivor Nicholas Whittle on the 25th anniversary of O’Brien’s and McGrath’s demise at the hands of the British army and Black and Tans.

In his memoirs, Nicky, one of the I.R.A.’s most ardent activists and strategists, recalling how he was about to be “finished” when the soldiers were suddenly distracted by Tom and turned on him, battering him with rifle butts. O’Brien was ultimately shot dead: a single bullet passing through his heart and lungs.

Arrangements had to be made so that Tom’s identity would not be revealed at the inquest held at the Waterford Military Barracks the following day. The I.R.A. approached his relatives and convinced them that secrecy was the best policy due to the necessity of hiding their movements from the enemy.

Though there was also the threat of reprisals against the family, Dunhill had some of the best fighting material in the Eastern Brigade. It was also rugged, hilly country, ideal for sheltering men “on the run”, so drawing attention to the area and the risk of raids was to be avoided at all costs. Whittle duly recognised the family’s patriotism in the face of their loss.

The findings of the inquest thus described Tom as an unknown. He was interred in the Republican plot at Ballygunner; his burial place recorded as “anonymous”. A military officer was reported to have advanced at the graveside to inspect the coffin to check if it had been inscribed. The breastplate was bare.

Tom was anything but indistinct to those who knew him. Among those were his team-mates. He had played football with Dunhill and hurling for Ballyduff; hence how he would have been helping his team-mates, the Powers, with the harvest in Kilmeaden. Also, he was a cousin of their neighbours, the Skehans, Carrigadustra.

The famous “Dunhill/O’Briens” minors, a dual combination from Dunhill and Ballyduff that won titles in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s, were named after Tommy, while the current Dunhill grounds, Páirc Uí Bhriain, were later dedicated to his memory.

Likewise, the Micheál MacCraith club in Tramore is called after his colleague who was also killed that night on the roadside at Ballinattin, where the Republican memorial was erected in 1922.

*My thanks to Riobard Eamonn Cinneide for identifying Tom in the threshing photograph, a print by Richard Fitzgerald published in 1998’s ‘Portrait of a Parish’ by Michael Carberry. The picture includes, at the back of the mill, from left – Tom Mackey, Willie Carberry, and Tom, side-on nearest the camera, and, on the mill – Maurice Curran with John and David Power.

Post Comment