‘The Antelope’ Davy Christopher

Tracking the career of little-known star sprinter and soccer trainer Davy Christopher

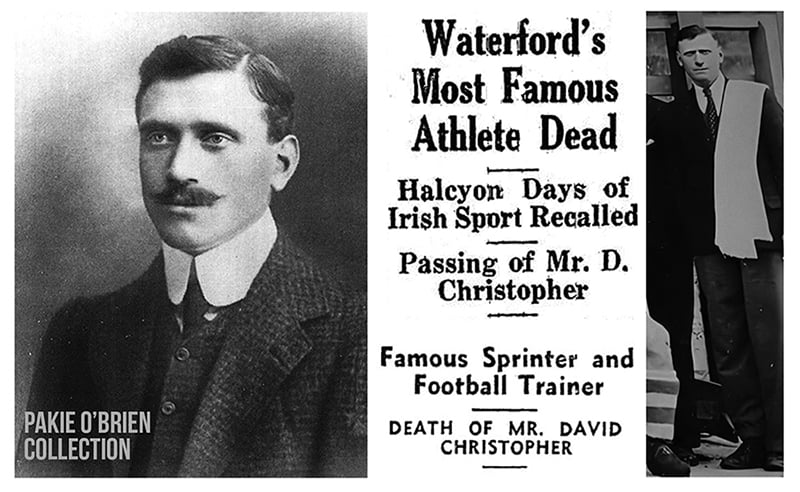

A Butlerstown man who became one of Waterford’s most celebrated sporting exports was laid to rest in Scotland amid little fanfare in early January 1950.

In marking the passing of a person whose historical footnote is seldom mentioned, the press reflected on David Christopher’s career and ‘imposing records’, calling him ‘one of the most naturally gifted runners of his time’.

But few who became familiar with him as a football coach knew just how brilliant he must have been in his prime.

The death of ‘Good Old Davy’ recalled an earlier halcyon era for Déise athletics, when locals, including the likes of de facto Olympic champion and triple-jumper Peter O’Connor from Waterford City (who held the world record for twenty-five years) and Percy and Rody Kirwan of Ballydurn near Kilmacthomas, more than held their own against the cream of international competition.

Brought up in Ballycashin, not far from Waterford City, Davy developed into an outstanding athlete at the turn of the 20th century, distinguishing himself in Ireland first and then Britain. Christened ‘The Antelope’ on account of his lithe, powerful running style and stamina, in today’s market he might well have been branded The Butlerstown Bullet.

He earned his race legs the hard way as a teenager at The Sweep, Kilmeaden against such noted names from that era as Ned Hartery and the Norris brothers, Pat and Joe. The Kilbarry AC member also stood out at the Goff Track in the People’s Park where crowds would gather for walking, running and cycling races.

Requiring nothing more expensive than decent shoes, and that more elusive purposeful stride, ‘pedestrianism’ (foot racing) was known as the sport of the people in those days.

Lightning off the mark, young Christopher proved an incomparable sprinter as an amateur and also dominated half-mile and mile events all over Ireland from 1894–98 (a period in which he joined the Waterford Artillery Militia).

David easily won the 880 Yards at Tipperary Athletic Grounds in September 1897 against a class All-Ireland field. The professional ranks were calling and at the end of the next season, he emigrated to Cardiff to make the most of his talents.

He scored a string of successes across the water. Also excelling in many competitions in England, Christopher moved to Scotland in 1903, winning ninety per cent of the races he entered there that year.

In 1905 his collection of wins spanned twenty race meetings, ranging from 120 to 1,000 yards. Pedestrian chronicles bear ample witness to his ‘exceptional versatility’ and ‘all-round excellence as a runner’.

Christopher would set a series of other bests in long and high jumps (once clearing 23ft 6 inches) and hammer throwing to confirm his prowess. And in the pro’ spiked-shoe arena, he needed to be as tough as old boots.

It was a cut-throat sport, with competitors routinely cheating to fix handicaps in their favour, sometimes putting lead in their soles to slow them down in the run-up to big races.

Gambling was a massive part of the business, with bookies and publicans paying for the keep (food, lodgings, training and physio) of most top sprinters, giving orders to lose when it suited that dare not be ignored.

HOME & AWAY

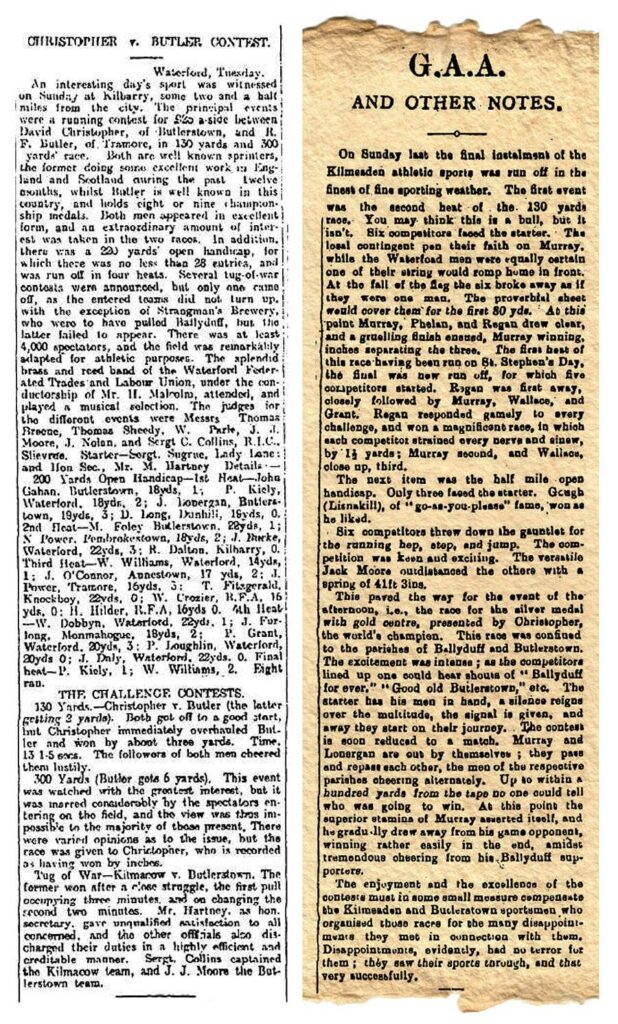

With his exploits overseas relayed back here, Davy was a big draw and in May of 1906 arrangements were made for him to return home to take part in a pair of races against the brilliant young Dunmore East athlete (and Royal Hotel, Waterford owner) Bobbie Butler at a Kilbarry sports meet in aid of the Christian Brothers’ Schools.

With special trains put on from Lismore and New Ross, around 4,000 people turned up to witness the men compete over two distances. Butler, a multiple provincial and national champion, was conceded a short advantage in each race but Christopher’s blinding bursts of speed blitzed both the 130 and 300 yards to claim the £50 purses.

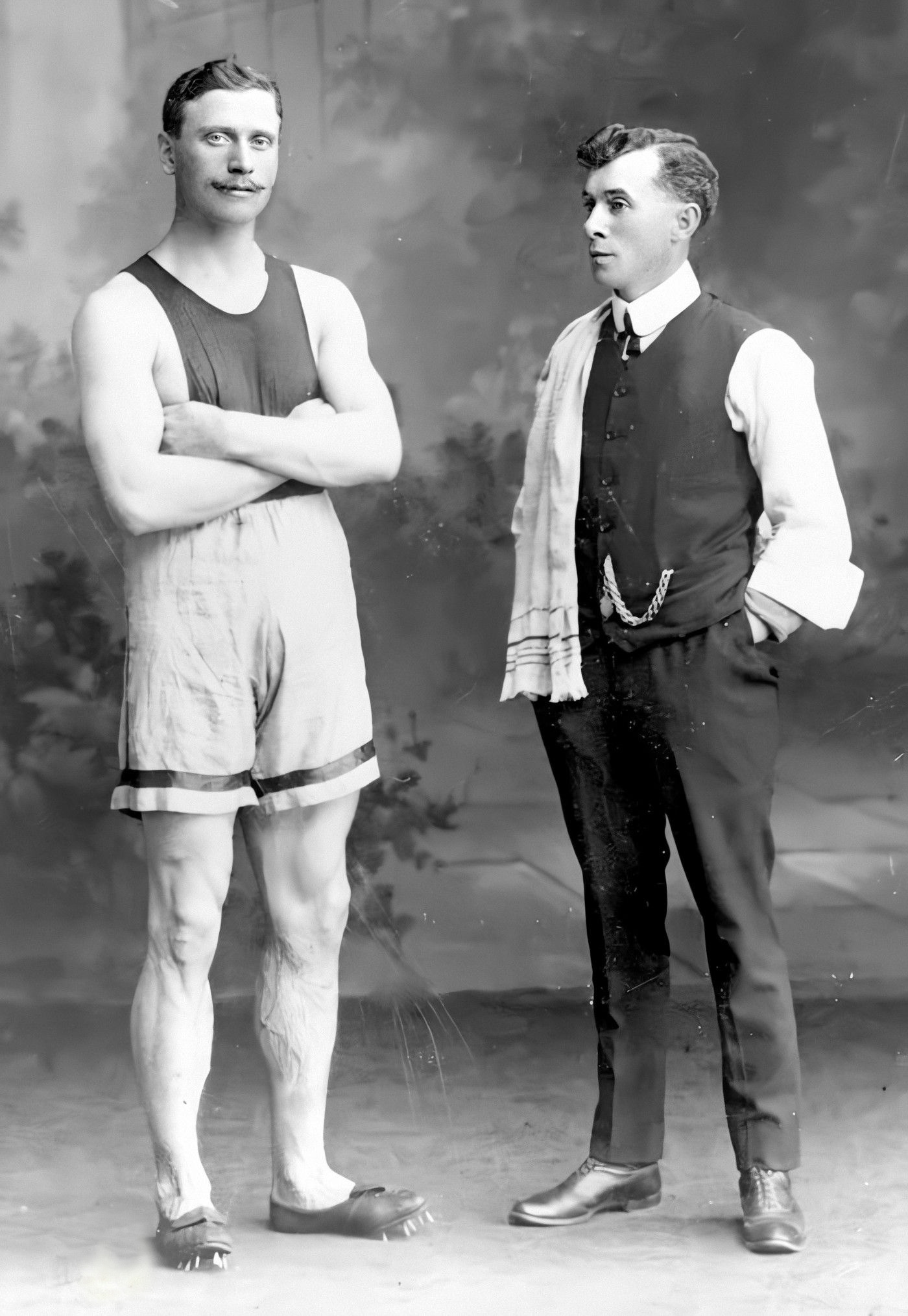

It was good preparation. That September he won the famous Pontypridd 130-yards sprint off scratch and a handsome cash prize. The prestigious Welsh Powderhall was the blue riband of professional sprinting, which Davy (known as ‘Dai’ across the water) took in a time of 12.5 seconds. A severe strain prevented him from defending his title at Taff Vale Park.

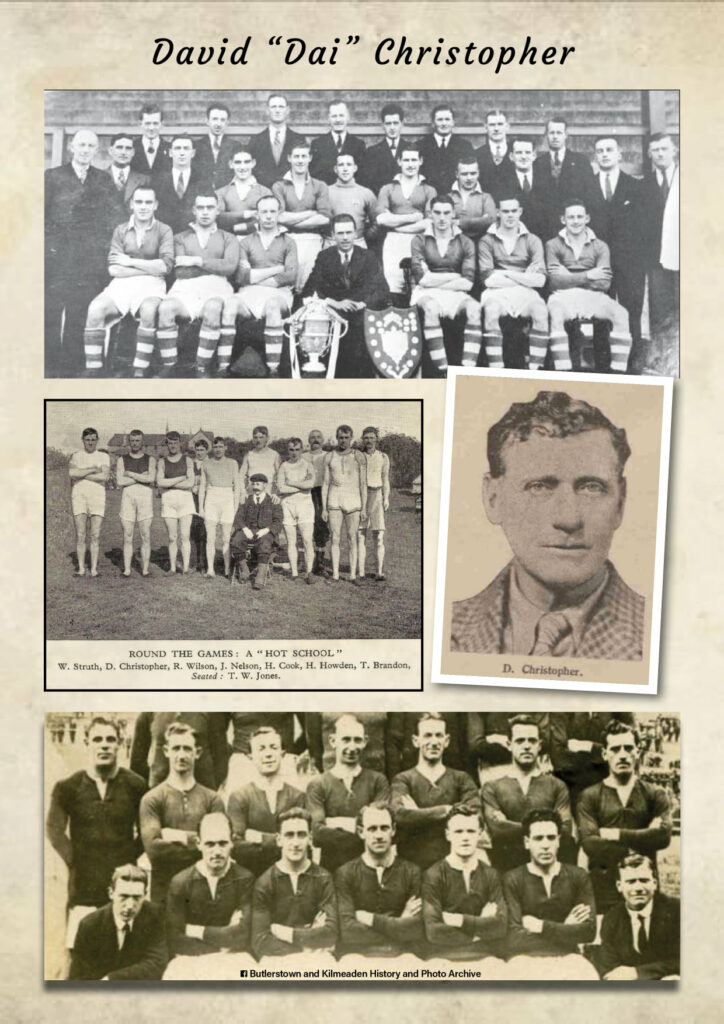

On moving to Edinburgh, Davy had been appointed a college sports coach and, as a fine footballer in his own right, he was also made trainer of the city’s first division soccer team, Hibernian FC; a position he filled for two decades between the wars.

He regularly travelled back here to visit his sisters (Ellen, wife of Joe Whitty, Ballycashin, and their sons Joe Jnr and Jim, and Kate, also in Butlerstown) and to meet up with other relations and friends in Waterford and across the Suir Estuary.

BLUES BOSS

When he agreed to come home to train Waterford FC in the summer of 1936, the Irish Independent reminded readers, in the politically incorrect manner of the time, that Christopher was ‘a great sprinter in his day. They still talk in Waterford of [his] victory in the 100 yards event over the coloured crack, Eastman. This was at a spot near the locally famous marshlands of Kilbarry, and [G.] Eastman was then achieving renown of the Jesse Owens’ variety.’

In fact, that race in July 1906 (described as a ‘magnificent’ duel by the Freeman’s Journal) had come a few weeks after the Butler head-to-head and a month before David’s Powderhall heroics.

Having trailed over the first hundred at Kilbarry, the Canadian/Indian challenger – dubbed the ‘black sprint champion of the world’ – reined in Christopher after a desperate struggle up the final thirty. The judges, under handicapper J.J. Moore, Whitfield (who started the two men off scratch) gave it as a dead heat.

The sprinters’ second scheduled race over 220 yards didn’t come off amid “unruly” scenes, with spectators breaching the roped cordon. It was postponed to the following Sunday but Eastman thought better of it and left for Liverpool in midweek.

Though he was well into middle age (and more than twenty years’ married) by the time he left Easter Road to take over as trainer-manager of his hometown soccer club in the mid-1930s, none of the Blues players could outpace Davy, whose ‘never to be forgotten’ impact raised the bar at Kilcohan Park.

A believer in ‘plenty of road work’ in the mornings and on-field sprinting in the afternoons, he only allowed the players to have the ball for practice once a week. His methods elevated the squad’s fitness to unseen levels, helping them to win the Free State Cup for the first time in 1937.

‘I expected the changes made in the team to work out satisfactorily, and so they did,’ he said after the win over St James’ Gate. His philosophy favoured fast football that let the ball do the work, with far-flung passes spreading the play to open spaces rather than ‘trying to walk the ball into the net’.

Steering Waterford to the Shield and League runners-up spot the following year, Davy was now in demand and was tempted by Shelbourne, who he guided to the same FAI Cup for the first time during a one-season stint in Dublin in 1939.

That spring he proudly trained a League of Ireland team to victory over a fancied Scottish selection. He returned to Kilcohan as trainer-manager a fortnight before WWII broke out and led the club to another cup final appearance in 1941.

SCOTS CLAN

He continued to make annual summertime trips to Scotland where he was almost regarded as one of their own (though he never shed the ‘old brogue’) and even got in some track coaching with up-and-coming athletics talents while there, as well as scouting soccer ones, of course.

A shrewd judge, he was instrumental in signing several big-name players from the UK and knew how to extract the most from the resources at his disposal.

‘We would win the Grand National with the type of training Christopher is giving us,’ Waterford captain John ‘Fatty’ Phelan told the Sunday Independent ahead of the decider against Cork United.

Though it ended in a replay defeat for a young Paddy Coad & co., main investor Willie Watt afterwards commended ‘good old Dave Christopher (left), “Fatty” and the boys,’ on their sterling efforts, which had also garnered a second-place finish in the table.

Waterford had finished level on points with Cork and only the inability to field a team in the play-off due to a dispute over payments to players prevented the realisation of chairman Gerry Whelan’s desire: that Davy’s faithful service would be rewarded with the League of Ireland trophy.

Alas, that never happened, with the Waterford directors taking the frankly ludicrous decision that very summer to resign from the League of Ireland until the end of the WWII Emergency.

During his latter spell on Suirside, the man referred to in the press as the ‘old ped’ had remained an interested spectator at local athletics fixtures, such as the Waterford AC Sports staged at Killotteran in September 1940, where one of his great admirers, Butlerstown’s Martin Hunt, was call steward.

However, Davy’s heart, and that of his Scottish wife, was back in East Lothian, where he wished to spend a well-earned retirement. However, after Helena died somewhat suddenly in 1947, her husband’s health went into serious decline.

The pensioner lived out the rest of his days with his son, Dr Wilford Kane Christopher, an RAF surgeon cum GP in the little dormitory town of Dunbar on the North Sea coast.

Sadly, just a few months after becoming a grandfather, Davy died in January 1950. He was in his mid-seventies, with countless miles on the clock since those early days at The Sweep.

Even if the authorities over within amateur and Olympic athletics circles ensured the professionals were written out of the record books, and mainstream sporting history, the local papers remembered ‘an exceptionally speedy youth on the track’ whose ‘fame became international’.

Famous for its ‘bracing air’, Dunbar is the final resting place of a man who ran like the wind.

Background notes

- Christopher was a surname common to County Waterford from the 13th century. After the Famine (1847-64) there were forty-seven households in Waterford bearing it, and there was but a minimal presence in only three other counties.

- From what I can tell, Davy’s parents were Patrick, a general labourer, and Johanna, née Keane. They married in 1872 and had five children, two of whom died young. They lived at Butlerstown South, close to the Castle, but later moved to Ballycashin.

- In 1911, the Christophers’ neighbours included Joe Whitty, and farmer siblings Michael and Margaret Carroll. Paddy was still working for farmers at age 78, and Joan, two years his senior, was also blessed by longevity.

- Ellen Christopher (b. 1889) worked as a servant for the Kearney farming family in Carrickphierish and her sister, Kate, married locally. Ellen was in her thirties when she married Joe Whitty from Nuke, Arthurstown, Co. Wexford, and they later lived at Ballycashin beside her parents in a little cottage not far from the local national school.

Post Comment