Pembrokestown MP ‘Derby Dick’ rode with Parnell

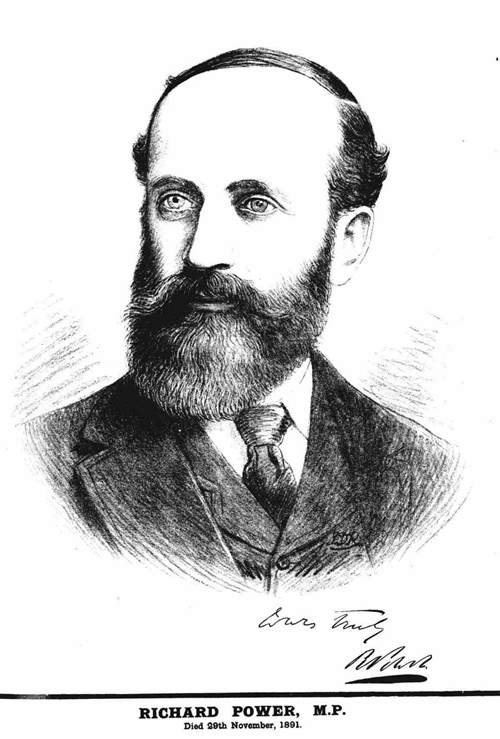

The short life of the Waterford nationalist M.P. Richard Power who rode side-by-side with Charles Stewart Parnell as a pioneering Irish Party whip in Westminster.

Barely 21 when he topped the poll for Isaac Butt’s original Home Rule Party in his maiden general election in 1874 , and doing so again in 1880, Irish Nationalist MP Richard Power represented Waterford City in the House of Commons for 17 years. And despite the latent colonial tensions of the time, he somehow achieved that rare political feat — universal popularity.

Dick’s parents were Patrick W. Power, a rich landlord and justice of the peace, who sat on the county grand jury, and his wife Ellen. The family homestead was Pembrokestown House, Butlerstown, which became a Power seat (passed down by Richard’s grandfather William) under a 500-year lease from the Esmonde family. They had acquired it through the 18th-century marriage of British aristocrat Sir James Esmonde and Ellice White, daughter of Thomas White, Pembrokestown.

Born in 1851 and educated at Carlow and Old Hall College, Hertfordshire, young Richard undoubtedly enjoyed a privileged upbringing. Other than being a firm believer in Ireland’s claim to be a nation, he had nothing to gain from a parliamentary career. Elections in that era were, as he often mentioned, a very expensive business. Politicians didn’t receive salaries and there were no expenses for travelling from Ireland to sittings in London.

He was well aware, however, that the worst off were at home: tenant-farmers denied ownership of the soil they toiled on, paying unjust rack-rents to alien landowners. Originally elected as a Home Rule League candidate, in one of his earliest debating contributions, Power observed that “under the present gorgeous system of government, only three sections of the [Irish] people thrive — the publicans, the pawnbrokers, and the lunatics”.

It drew laughter, but the Commons newcomer, who matched an economist’s grasp of statistics with a wordy but quirky command of language, scolded that this “so-called Union” had resulted in an Ireland riven by emigration and pauperism.

“A union to be lasting,” he said, “must be founded on the self-interest and friendship of both countries”. Power’s political perspective barely altered from that simple rationale.

Forming a fast personal friendship with Irish Party leader and Anglican Wicklow aristocrat Charles Stewart Parnell, they sought to pursue Home Rule whilst striving to reassure English voters that independence would be no threat to them.

When Parnell, the great agitator — “whose teachings have set the whole country ablaze” — paid his first visit to Waterford for a massive Land League rally in early December 1880, the city was en fête. Special trains and steamers were put on, and a large force of police and troops was also drafted in.

With banners hailing “C.S.” as “Ireland’s future President”, he, Power and the second Waterford city MP Edmund Leamy were cheered to the echo as the mayor’s carriage made its way into town amid a spectacular and racously-received procession.

It was led by 75 horsemen representing the farming community, followed, on foot, by agricultural labourers. A monster meeting was held on the Hill of Ballybricken, a stronghold of radical nationalism, where an estimated 40,000 people gathered on the green.

Opponents tried to portray a poor turnout of the very tenant farmers Parnell came to cajole — a mischievous ‘Waterford Standard’ editorial claiming these men, “contented and prosperous under the generous landlords [were] conspicuous by their absence”.

The paper also delighted in the rich irony it saw in Parnell entering “the enemy’s camp” to join the Marquis of Waterford and a host of other landed gentlemen — Richard Power included — in hunting with the Curraghmore hounds at Ballinamona during his stay.

The reality was that more than half that hunt was made up of gentlemen from the city; major Power supporters and party donors. Another aspect to this poisoned dart was the fact that Joseph Fisher, proprietor of the rival Munster Express and Waterford Daily Mail, was president of the city’s Land League branch.

Power was beloved of the Irish National League, his party’s promoters-in-chief and an alliance of tenant-farmers, shopkeepers and publicans. They recognised his influence, intellect, and good intentions.

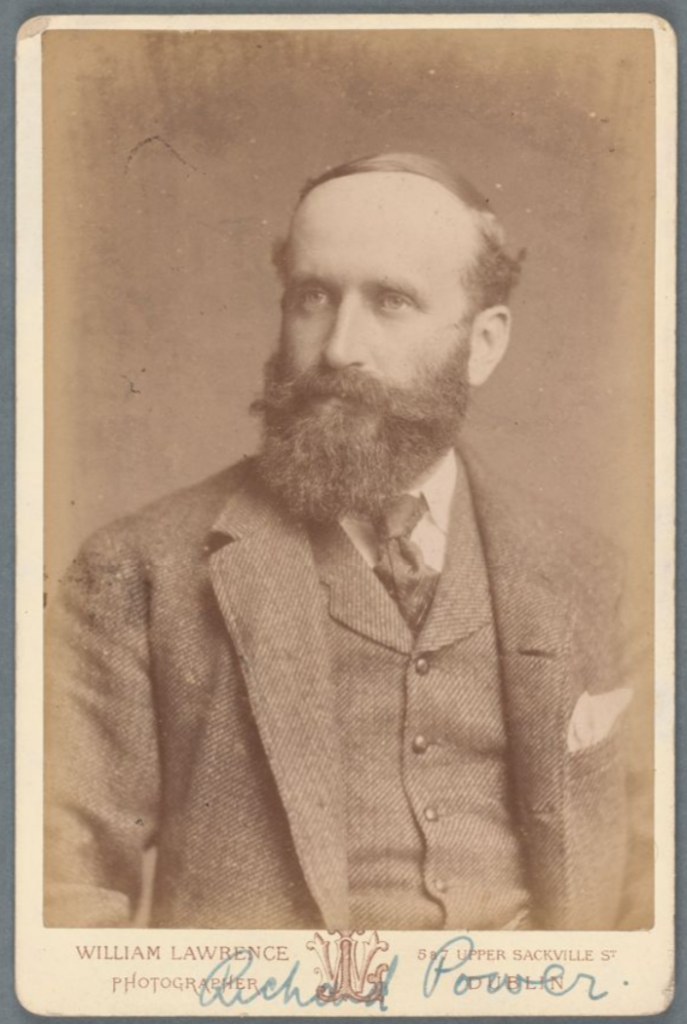

[National Library of Ireland]

Entrusted with instilling discipline within a tightly organised outfit, Richard had become the Irish Parliamentary Party senior whip in Westminster in 1878 — one of the first such roles in western politics.

It was a difficult job but Power’s earthy popularity and honest-broker credentials kept the peace for a dozen years — a period in which Parnell, with his help, created Britain’s first modern, disciplined, party-political machine; harnessing nationalism at home and Irish-America to finance the cause.

A vote-getter as well as a peace-broker, in the famous landslide election of 1885, Richard Power was one of 87 Home Rule members returned out of 102 seats in Ireland. He polled 3,000-odd votes versus 300 for the Unionist candidate, Fitzmaurice Gustavus Bloomfield from Ferrybank.

The outcome gave Parnell’s party the balance of power between the Liberals and the Tories and they effected it by pioneering the whip system. Dick oversaw every MP’s pledge to “sit, vote and act as directed”.

There was prolonged cheering when the Waterford result was called out by City High Sheriff Andrew Farrell to a teeming Mall in front of City Hall. Power thanked his constituents “in one of those practical, pithy, and poetic speeches so peculiarly his own”, the Munster Express reported.

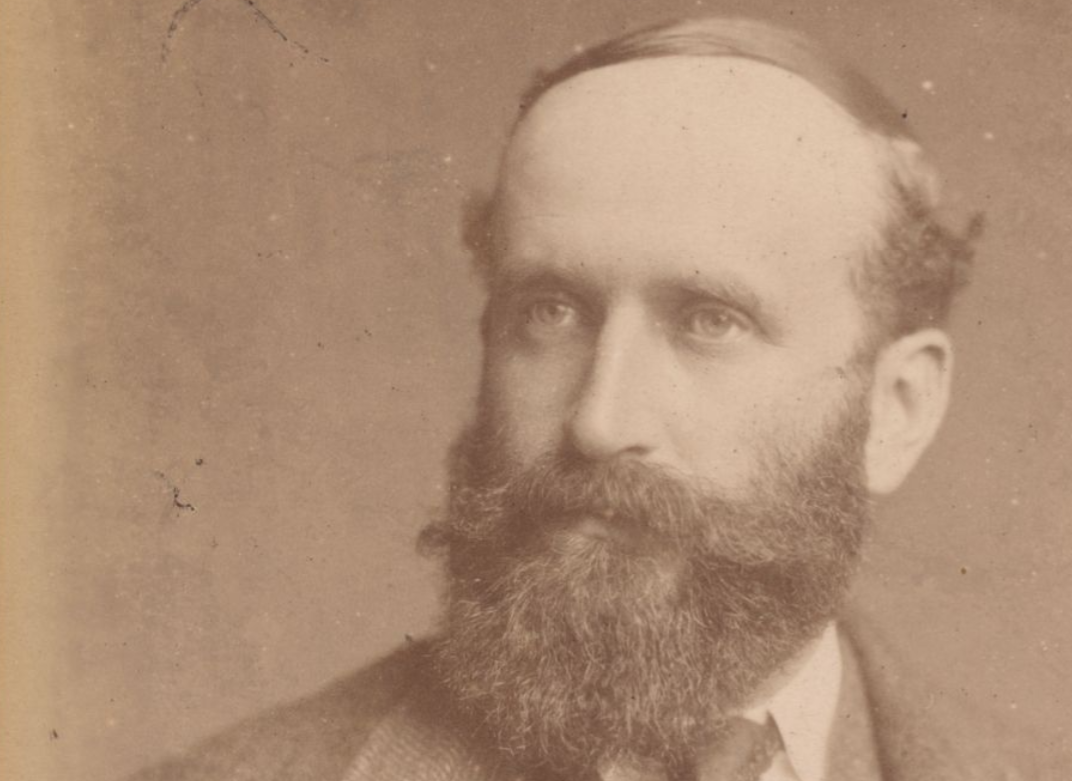

[Copyright: Trinity College Dublin]

Waterford city voters were more nationalist than those in the county, whose representatives were felt to be half-hearted about the Irish ideals of tenant rights, home rule, and Sunday closing — not to mention their overt Englishness.

To the locals, Power was one of their ilk, known as “Master Dick” among farmers and labourers, and “Sporting Dick Power” to his acquaintances farther afield. These pals included the Prince of Wales, who regularly hosted him at breakfast parties, fascinated by his knowledge of horses.

Power was famously given the moniker “Derby Dick” for carrying the adjournment of the House in May 1878, urging that members be allowed the day off to enjoy the ancient thrills at Epsom Downs.

He argued that “no sane man could have any hesitation” of choosing “the indescribable pleasure of seeing the noblest horses in the world coming round Tattenham Corner and making for the winning-post amid the shouts of thousands” over the “bad air, dull repetition, and tiresome talking” in Westminster.

An advocate of the “manly” maxim, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”, Power decried the fact that legislators had “already made penal nearly all the sports and pastimes of our ancestors — cock-fighting, dog-fighting, bull-baiting, man-fighting, and nearly all kinds of fighting except that of armies, when one-half the world is prepared to slaughter the other half in the name of civilization”.

Dick’s proposition to take Derby Day off became an annual event in itself. “Men of all stations, creeds, and classes, shared alike this sport,” he reiterated before the 1880 edition. Epsom was a neutral ground where all religious and political differences were buried, he said. He only wished they had some such burial-ground in Ireland.

A decade later, Power had had enough of speech-making and campaigning. He had let it be known that he didn’t intend to seek re-election, which seemed assured had he decided to run again.

He’d just persuaded Waterford’s militant trades and labour movement — which mounted a dozen industrial disputes in 1890 alone — to overwhelmingly support Parnell’s policies, aimed at securing a new Home Rule Bill, which was tantalisingly within reach.

But then the IPP blew apart into Parnellite and anti-Parnellite factions. The cause was Charles’s long-time lover, the English wife of a Clare colleague, Captain William O’Shea MP.

Named in the divorce action, in the summer of ’91 Parnell married Katharine O’Shea (Kitty to her enemies), mother of his three children. It prompted Catholic scandal in Victorian society and his downfall as Irish Party leader.

Charles died just four months later — not just broken by the toll of a venomously-divisive by-election tour of Ireland, but physically spent too, succumbing to stomach cancer at 45.

Despite tensions roused by Richard’s independent and often-questioning mind, the mutual admiration between Parnell and Power endured to the end.

Surrounded by 200,000 mourners, Dick had stood beside Parnell’s open grave at Glasnevin with tears running down his cheeks in early October 1891. Perhaps he’d sensed his own mortality.

“Never of robust constitution,” Power had taken seriously ill himself the previous year, but after recuperating in the south of France during the winter, he came home in April 1891 in good spirits, if looking unwell.

His optimism intact, in mid-November he married his fiancée Annie O’Donnell from Carrick-on-Suir, and the couple went on honeymoon to London. While there, Dick contracted a severe chill in a theatre, having initially caught cold at Parnell’s rain-drenched Dublin funeral.

A long-standing problem, which caused his lungs to hemorrhage, erupted in earnest, confining him to bed at The Grand Hotel. This time his trouble was terminal.

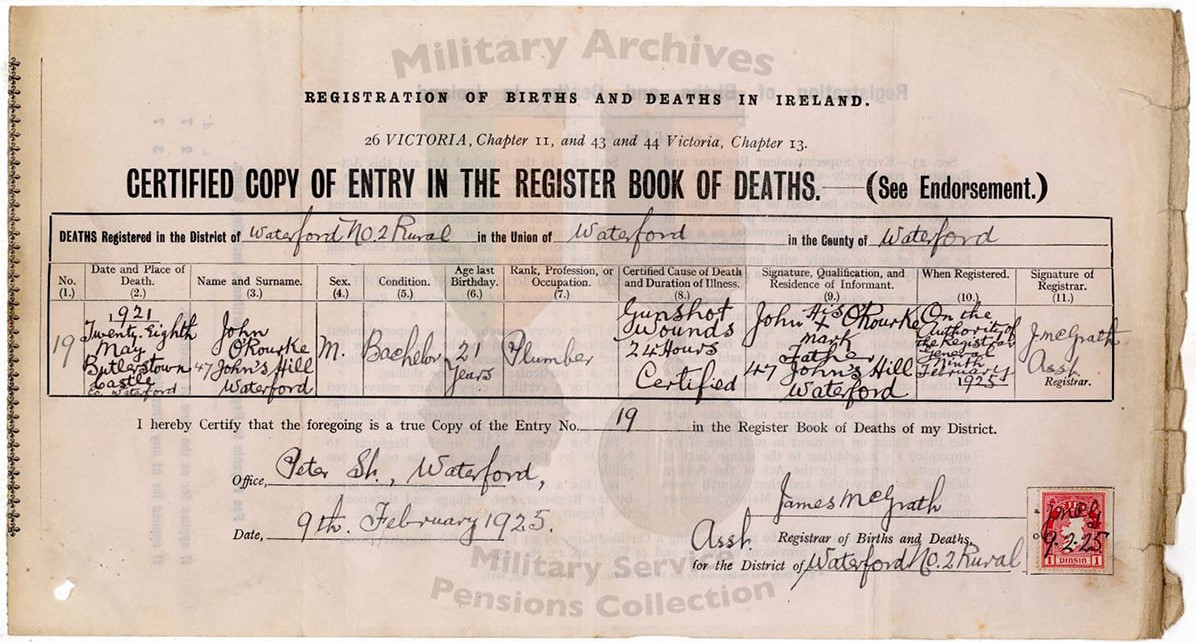

Power sent word to his brother Edward, district coroner based in Tramore, telling him to travel over without delay. He got there just before Dick died, officially of pleurisy. The telegram announcing the news was sent home by Annie Power, Dick’s new wife of one week and now his widow.

The Munster Express editorial expressed the sense of shock among his constituents: “Man met man in streets, lanes and alleys of Waterford on Monday morning, and simultaneously said: ‘Is it true that Richard Power is dead?’”

Richard’s remains were brought to Dublin by steamer, where they were met by, among others, Wexford MP John Redmond, who would soon assume Power’s seat. On arriving by train into Waterford that Tuesday, they were met by upwards of 6,000 people on the bridge. Every business in the city was shuttered.

Thousands more attended his funeral. Such was the size of the procession that by the time it reached Tramore — mourners having to wade through deep water en route — there was pitch darkness and the burial had to be postponed until the next morning.

The extensive tributes in the press read as genuine. The Munster Express said: “We may with all truth say that Richard Power had not one enemy or evil-wisher in the wide world. His was a noble, generous nature, kind and thoughtful courteous and refined — a gentleman every inch of him”.

In a statement, the United Ireland association mourned the loss of a man “beloved his own people of Waterford, rich and poor, and by colleagues with whom he had worked for Irish liberty through many dark and trying years”.

Redmond, who’d contested and lost the by-election in Cork City arising from Parnell’s death, profited electorally from Power’s passing. In 1900 he reunited the party that Dick had managed to keep a rein on until his and Parnell’s parallel race for Irish autonomy was run.

When Richard’s father Paddy died in May 1894, a year after a new Home Rule Bill was introduced, the grand but secluded 8-bedroom house and 100-acre farm was initially put up for auction, before being taken over by his other son Ed and family.

Post Comment