Uncovering Blackwater roots of real-life ‘Rocky’ Quarry

Jamie O’Keeffe on the back-story and career of a born boxer who was once the latest heavyweight ‘Great White Hope’ and ultimately too brave for his own good.

Long before Conor McGregor brought his controversial brand of ‘fighting Irish’ to the United States, countless others with a direct or distant link to the Emerald Isle – from the ‘Cinderella Man’, Jimmy Braddock to Connemara’s Seán Mannion – won the hearts of American boxing fans through true grit rather than false machismo.

Among them was ‘Irish’ Jerry Quarry, whose death in 1999 was attributed to the same killer condition – repeated punches in the head – that gradually did for Muhammad Ali.

Quarry’s paternal grandfather hailed from rural Kinsalebeg in West Waterford. It’s almost two decades since that connection was confirmed by way of a chance excavation on the Portláirge side of Youghal Bay.

In early 1998, the Irish Examiner carried a short report from local freelance journalist Christy Parker. He told how neighbours Claude Fitzgerald and Padraig Daly were clearing a ditch to get stepping stones for a hill garden Claude was building on his property at Prospect Hall House, Ferrypoint, on the banks of the beautiful Blackwater.

The JCB digger they were using unearthed a sandstone slab, thought to have been part of a gateway entrance, with the words ‘Thomas Quarry, 1876’ clearly inscribed.

Researching the discovery, they found that the Quarry family had farmed 18 acres in Kinsalebeg before emigrating to the States in the late 19th century. Thomas, it turned out, was the grand-uncle of a man who would establish himself as one of the biggest draws, and the best uncrowned contender, in the halcyon days of boxing’s heavyweight division.

I was a journalist with the Dungarvan Observer newspaper at the time (Christy being a regular contributor) and the piece piqued my interest. Trawling the ‘Observer’ archives, I spotted the following paragraph in the West Waterford notes from December 1973 — “Following recent victories over outstanding opponents, Jerry Quarry (U.S.A.) is again in contention for the World Heavyweight Boxing title and is expected to meet [George] Foreman early in the New Year. Quarry’s grandfather came from Kinsalebeg Parish.”

So the connection was already known; but now it was now set in stone, as it were.

EMIGRANT’S TALE

Doing some more ‘digging’, records verified that Thomas’s brother, John (Jack Paschal, born in 1884), who lived in the house as well, had crossed the Atlantic to Ardmore, Oklahoma, and married an Irish woman, Jeanetta Conway from Arkansas.

A son of theirs, Jack, Jerry’s dad, was born in 1922 and worked as a hobo labourer. A skin condition had thwarted Jack jnr’s promising amateur boxing career (his sores were so bad he was too embarrassed to wear shorts) and he struggled instead to make ends meet in desert work camps; bare-knuckle brawling all-comers for cash along the way. He wanted more for his sons. They would get better, but also much worse.

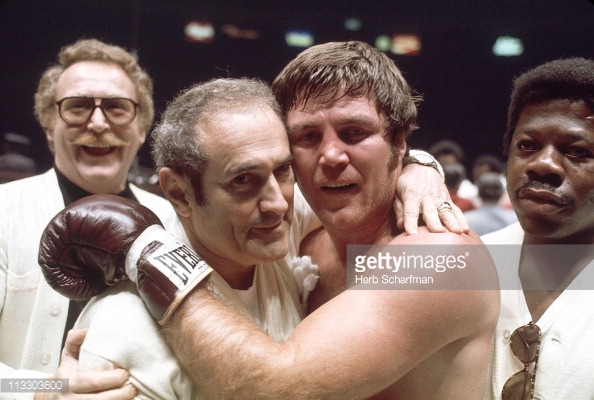

[Photo by Herb Scharfman/Getty Images]

From infancy, Jack trained them to fight, often each other, though they revelled in their old man’s tough-love tutelage. “There’s no quit in a Quarry,” he told the boys, who wondered why the words “Hard Luck” were tattooed on his knuckles.

The endless sparring sessions he oversaw at home, and when they later moved gym to Miami Beach, were beyond barbaric, according to onlookers. They included a young amateur fighter and budding actor called Philip (aka Mickey) Rourke, whose own destructive passion for boxing would return to help ruin his face and film career.

Initially it seemed as if Jack’s school of hard knocks had paid off. Jerry became National Golden Gloves champion at 19 (setting a record by knocking out his five opponents in the space of three days) and his square-built punching power and Gene Tunney looks quickly made him the most popular professional of the late sixties; a period when the ‘Great White Hope’ tag carried social connotations.

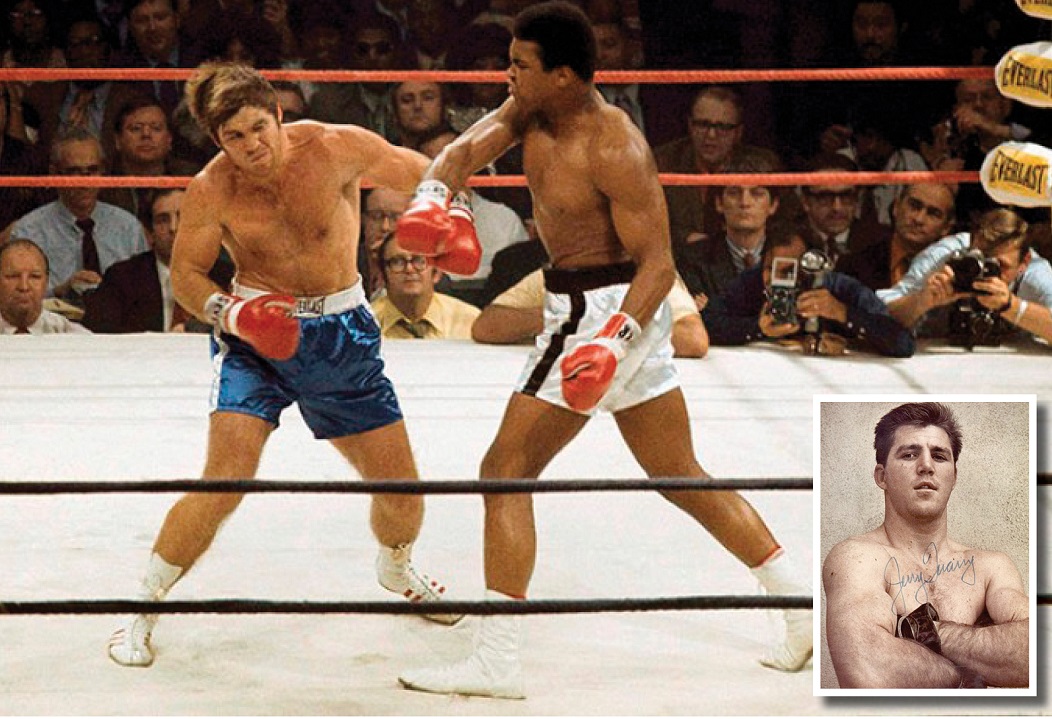

‘Irish Jerry Quarry’ was box office and, though erratic and occasionally more fragile of mind than body, he generally lived up to his billing. He was prepared to mix it with anyone and, by George Foreman’s own admission, posed a threat best avoided. The only man to take on both Ali and Joe Frazier twice (unfortunately for Quarry, he met them in their heyday) the ‘Bellflower Bomber’ was the one top-ranked heavyweight with the guts to put it up to the former Cassius Clay on his comeback in 1970.

In agreeing to be Ali’s first opponent after an enforced three-year exile for refusing the Vietnam draft, Quarry was a central figure in the most anticipated event in sports history up to that point. Amid a charged atmosphere in Atlanta, Georgia, then centre of the civil rights movement, the place was black, figuratively and literally. The crowd wanted Jerry’s blood and they got it. His eye in ribbons, the cut-prone ‘Californian Celt’ was “whupped” in a 3-round TKO.

The “fall-guy” picked up his biggest payday ($338,000) but insisted he hadn’t done himself justice. And so there were few complaints when the all-action Quarry, who had thin skin but a granite chin, was granted a re-match in Las Vegas in 1972.

However, a near-fatal knockout of his brother Mike on the undercard left Jerry “destroyed” before his second swipe at Ali even started. Amid another racially-inflamed affair, he was mercifully stopped in the seventh by the referee on the urgings of a masterful Muhammad: on a mission to avenge his loss to Joe Frazier the previous year.

Though while their ring relations appeared hostile, Quarry held no grudges and would later call on an uncanny impression of “the greatest of all times” during stints as a co-commentator. Likewise, Ali – who defeated Alvin Lewis at Croke Park, Dublin, just three weeks after besting Jerry a second time – retained a lot of affection for “a very good man” whose accelerated demise, of course, mirrored his own.

FAMILY MISFORTUNES

A veteran of 200 amateur and 50 pro fights by age 26 – mixing stunning victories (such as those over Floyd Patterson, Ron Lyle, Buster Mathis and Ernie Shavers) with frustrating defeats – a jaded Jerry hung up his gloves in 1975. He became a pop band bodyguard, and made a decent fist of guest commentary, TV acting roles and movie parts.

Sadly, for all the lucidity and wit he demonstrated on screen, Quarry, who made $2.1m in the ring, was something of a party animal outside it, with abundant access to alcohol, cocaine, and women. That was bad enough, but blinded by the lure of the limelight, he couldn’t resist stepping back inside the ropes, unable to see that his once-appealing “all-American” brand was past tense.

His supposed final bow came as a cruiserweight in 1983, despite already showing obvious signs of trauma-induced brain damage. The Bakersfield lad who’d single-handedly sold magazines in his pomp, and counted Elvis and Sinatra among his closest pals, was now a washed-up shell.

Married and a parent three times over, by 1992 Quarry – who’d come from poverty and made and blown a fortune – was alone, broke, and losing his mind and motor skills. Feeling betrayed by boxing but inspired by George Foreman’s unlikely revival, shamefully Jerry somehow wangled another payday aged 47. For a pitiful thousand bucks, his career concluded as a human punchbag.

[Photo by Bob Riha Jr/WireImage/Getty Images]

Rapidly deteriorating into an Alzheimer’s-like state, Quarry was virtually oblivious when inducted into Boxing’s Hall of Fame five years later. Penniless, and left with “the temperament of a twelve-year-old,” by the time he died, seven years ahead of his father, Jerry had become a poster boy for the sport’s abolitionists.

He was cared for in his final years by Jimmy, his one-time cornerman and the only brother among “The Quarrelsome Quarrys” not to box professionally. Recalling his those final flurries in the ring, James said: “In making those comebacks, Jerry would walk around saying, ‘I’m going to be a hero again.’”

Mike Quarry, once rated the world’s second-best light-heavyweight, was also struck down by Dementia Pugilistica in later life and died in 2006. Their other brother, former heavyweight Bobby, 54, suffers from Parkinson’s today, having exhibited ‘punch drunk’ symptoms since his early thirties.

Smokin’ Joe Frazier, who beat Jerry in a 1969 ‘fight of the year’ to retain his belt, said that behind the “good-looking Irish kid with a nice smile” lay “a very tough man – he could have been a world champion, but he cut too easily.”

Not to mention the fact that he fought too much. Jerry eventually endured 62 pro bouts (53–9–4), many of them flat-out slugfests, during his 1965–’75 prime, the brutal ‘Golden Age’ of heavyweights. “I’d do it all again, same way,” he said in the mid-nineties, oblivious to the fact that the sport, and his ingrained style, had, according to one neuropsychologist, aged him 30 years.

The Jerry Quarry story is a cautionary tale of triumph and tragedy. He was taught never to quit. It took him to the top. But the lesson is that it was his downfall too.

Post Comment