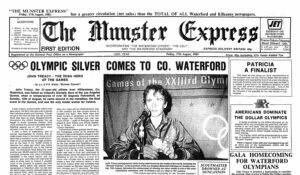

LA legend Treacy’s silver lining in greatest marathon ever

John Treacy’s time in Los Angeles 30 years ago would have been good enough for gold in every subsequent Olympic Games until 2008, writes Jamie O’Keeffe

“And for the 13th time, an Olympic medal goes to John Treacy from Villierstown in Waterford. The little man with the big heart.”

Thus went the immortal acclamation of RTÉ’s self-styled ‘Memory Man’, Jimmy Magee, a split second after reeling off the 12 previous Irish Olympic medalists as John Treacy shuffle-sprinted the last 100 metres of the Marathon on the final evening of the 1984 Games in Los Angeles — 30 years ago last August 12th.

Eleven at the time and sports-mad, because it was during the summer holidays I was allowed to stay up until the small hours of that Monday to watch history unfold and listen to Magee’s legendary list. “The crowd stands to the man from Villierstown in Waterford. My fellow commentators are on their feet. It is quite remarkable…”

A local legend, international junior and collegiate ace, and back-to-back winner of the senior World Cross-Country title, Treacy was already the pride of his village, county, and Ireland. When he crossed the finish line that night, an exhausted mingle of pain, sweat and emotion, everyone in global athletics knew the 27-year-old’s name.

Bereft of form or fortune for several seasons, in the autumn of 1983 Treacy, by now employed with Córas Trachtála, the Irish trade board, decided to relocate back to the States and his Alma mater, Rhode Island’s Providence College. It was there he had been a star on the university circuit alongside a raft of other fleet-footed Irish students, several of whom also hailed from Waterford.

Taking his wife and baby daughter with him, Treacy knew that to have any chance of fulfilling his potential at Olympic level he needed to get back to the collegiate-type set-up where he’d flourished thanks to top-class training partners, professional coaching, and cutting-edge physiological and nutritional advice.

He had true grit in spades but Treacy believed in the appliance of science too. With a meticulous mind behind those glasses, he did his long runs every week at the exact same time of day as the Olympic Marathon would take place. He even took into account the time change from east coast to west coast so his body would be perfectly adjusted cometh the hour.

Treacy had the will but he knew the way as well.

SECRET MISSION

The marathon was scheduled just five days after he trailed in ninth, and deeply disappointed, in the 10,000m final — prompting some criticism from the usual all-conquering quarters. Indeed, athletics correspondent Tom O’Riordan wrote in the Sunday Independent on the morning of the marathon that “Many are of the opinion that Treacy is unwise to run in this event”. Few knew it was his real goal going to the Games all along.

In saying that, O’Riordan pointed to the common wisdom that “an athlete can run a great race in his first marathon” — or, he neglected to mention, a stinker — and that secretly Treacy had been preparing for it since February; even running 29 miles on night in training “without feeling any after-effects” and jogging 126 miles a week since the previous October.

In reality he’d probably been thinking about it as far back as his dehydrated collapse at Moscow 1980, since when little had gone to plan.

“I used to get very annoyed with myself and I jogged twice a day between the 10,000m final and the marathon,” Treacy recalled in 2003 at an evening hosted by Irish Runner Magazine to mark the 25th anniversary of his first World Cross-Country triumph. “Once my mind was made up I was very determined. My mentality was a medal or nothing.”

Unlike the nervousness he felt on the track, “I was completely relaxed before the marathon. The pressure was off. Nobody was expecting anything of me but inside I was still superbly confident because I really had done my work and I knew I was in fantastic shape.” (Try 9st 4lb and 5.5% bodyfat for size.)

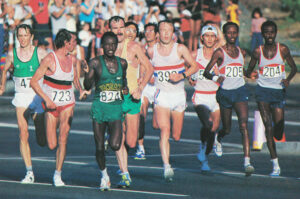

And so onto the freeways of California that climactic Sunday, up against 107 other runners in what’s widely considered one of the the best marathon fields ever assembled.

“I said what I would do was try to follow some of the favourites,” Treacy figured. “So I followed [Alberto] Salazar [the hot American fancy and World Record holder] for the first 5km before realising he wasn’t going very well. I then saw [World Champion, the Japanese Toshihoko] Seko up the road so I followed him instead.

“You try to bury yourself in the pack in a race like that and drink plenty of water early on. At halfway, I found myself still up with the leaders. Charlie Spedding [of England, winner of the London and Houston Marathons earlier that year] was the first to make a move.”

RECORD PACE

Among the front-runners was Carlos Lopes, a veteran Portuguese and also a two-time winner of the World Cross-Country Championships, but equally not regarded as a candidate for gold. Aged 37, and only just recovered from a minor traffic accident, he’d only completed one marathon before. Though that was one more than Treacy, who had never even competed over the distance.

Even still, used to a faster pace over the shorter distances, he felt like he was taking “a Sunday stroll” for a long while. At around the midway point he drifted into the lead but decided it was no time to try to be a hero, and settled back into the pack. Five miles out, he was one of a handful whose tempo had separated the strongest from the also rans.

Then there were four — the hotly-tipped Robert de Castella of Australia falling behind as they clipped along at 4:40/mile pace. Treacy was still “very comfortable” at 20 miles (“What ‘wall’?” he joked afterwards) before Lopes made his decisive break with around three miles remaining.

“It felt as though I was sprinting beside him and so I made the decision to let him go. Charlie Spedding and I managed to get away from the rest of the pack and I knew that if we stuck together and didn’t do anything stupid I would get a medal.

“However, we got a severe fright one mile out when we both noticed a shadow appear right behind us. Charlie and I looked round in shock but were relieved to see that it was only the boom of the TV camera!”

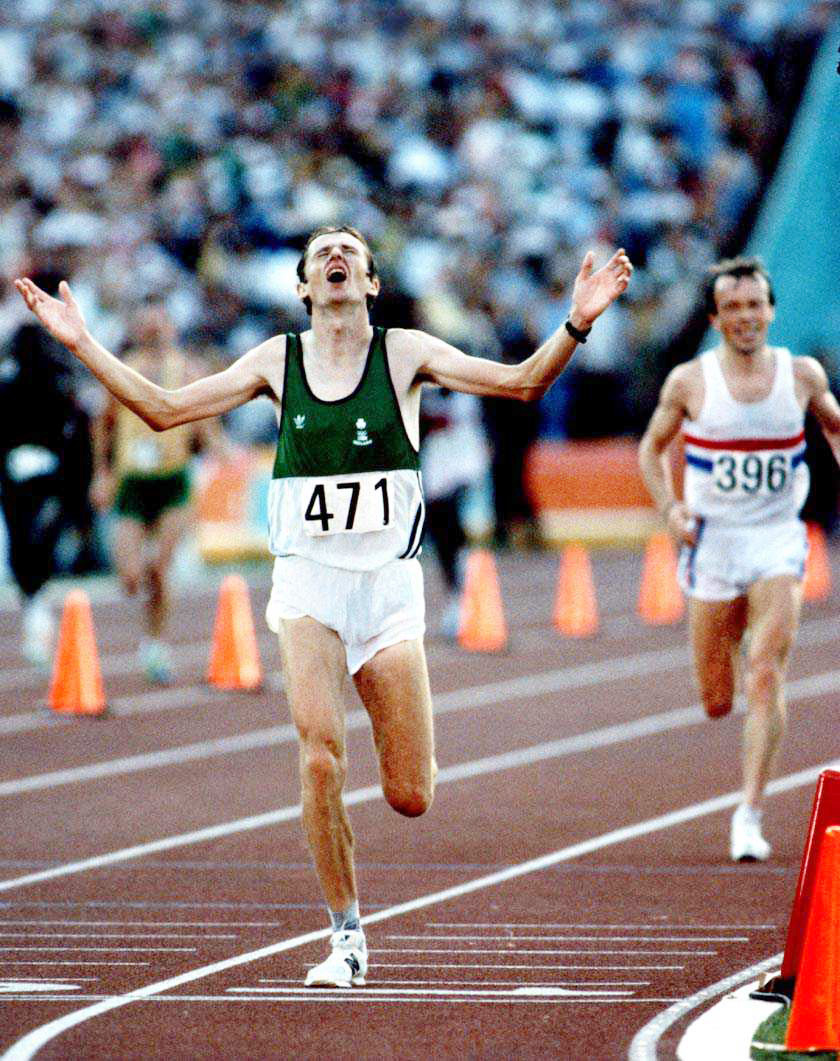

Lopes entered the main arena in what was, by that stage of exertion, an unassailable lead. Then RTÉ viewers heard the roar.

“And John Treacy appears in the stadium! — 471!” boomed Magee as the noise of the crowd upped several notches. With the marathon finale choreographed to be part of the closing ceremony for the first time, that the three medalists were now running on the track together heightened the atmosphere.

“He’s very tired,” interjected co-commentator Tony O’Donoghue. “He’s tired but he’s great and he’s good and he’s hanging on,” an undaunted Magee countered, preparing his famous roll-call of those who had come before.

Never what you might call a stylist, the deceptively frail-looking Treacy, having decided to make his surge for silver before entering the packed 92,000-capacity Coliseum (“as I wanted to savour the moment”), managed to put in an incredible 67-second last lap,

Treacy’s kick eventually burned the Briton off and he crossed the line overwhelmed by “a sense of relief — and then the joy obviously.” The feeling of self-fulfillment struck as soon as he was alone with his thoughts. Given the festivities going on all around them, the podium presentation was extra-special — “a fantastic moment,” he reflected.

ANGER MANAGEMENT

The fact Treacy came home just 35 seconds shy of first place prompted some to suggest he could have won had he not run in the 10,000. He saw it another way, telling the media the next day: “I was angry after doing so badly in that final. I wanted to prove something.”

The Los Angeles Times reported “astonishment” at what Treacy had achieved, “passing history’s fastest marathoners … as if they were stragglers in a weekend 10K race.”

Broadcasters ABC television called the top three placings “a shocking upset”. Maybe so, but the facts brook little argument. This was no flukey performance in mediocre company. Lopes had set a new Olympic Record that would stand for almost a quarter-of-a-century.

Indeed, despite the oppressive 85-degrees F heat and humidity — a far cry from the winter quagmires where he made his name — Treacy’s own time of 2:09:56 (knocking over 2:20 off the Irish record) would have been good enough for gold in every subsequent Olympics until 2008; while ninth-placed Jerry Kiernan’s 2:12:20 would have won the 1992 and ’96 editions.

Looking back, “I feel that I got as much out of myself as I could,” said Treacy, who learned the lessons from his dramatic demise in the Lenin Stadium four years before. He hydrated heavily in the days beforehand and shrewdly wore a cap to shield himself from the harshest temperatures before discarding it later on as the sun went down.

“I was tested a few days later for microscopic tears and apparently after a hard session you would have between 300 and 400. I had 3,500 — I had run myself to a standstill.”

Main photo: John Treacy crosses the line in LA. Photo: George Herringshaw

Post Comment