Parnell’s Westminster ally Biggar and Butlerstown Castle

Butlerstown Castle and key Parnell ally who could bore for Ireland

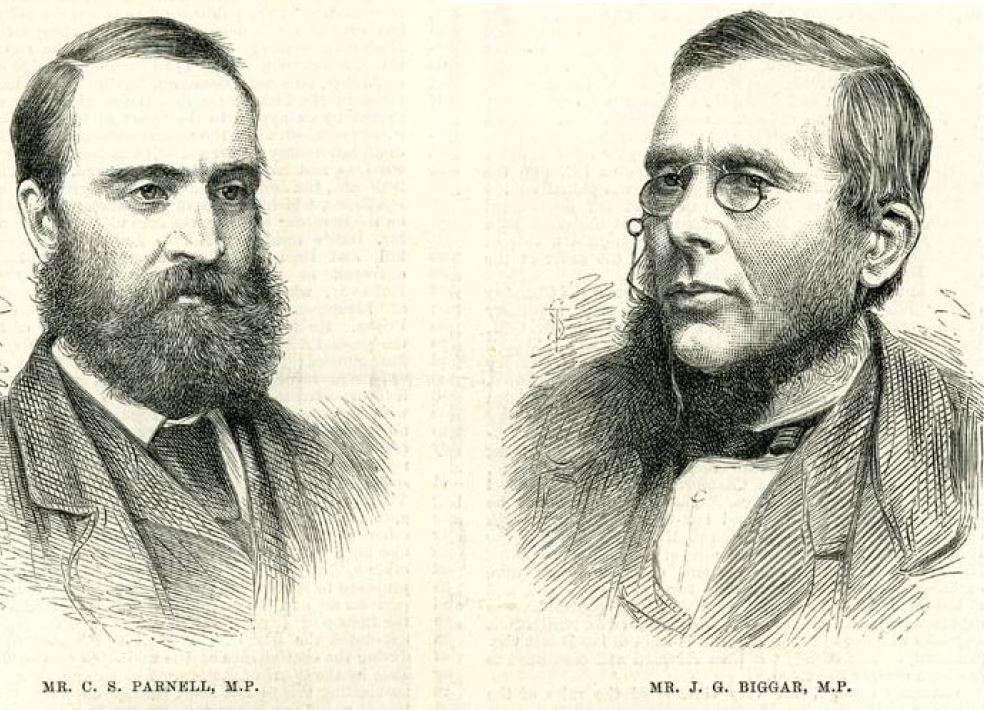

AMONG the many owners and occupants of Butlerstown Castle in County Waterford down the centuries was a diminutive and eccentric Northern nationalist by the name of Joe Biggar; little-heralded “right-hand man” of Irish political heavyweight Charles Stewart Parnell and one of the greatest time-wasters ever heard in Westminster.

Born in 1828 and from a Belfast merchant-prince background, long before entering politics, Biggar — more commonly known as Joe, or J.G. (Joseph Gillis) — established himself as a successful provision trader nicknamed “The Belfast Pork Butcher.”

Rejecting the need for a classical education, he insisted selling pigmeat on commission on the mean streets of his native city gave him a sufficient command of the English language as he needed to talk ad nauseam about everything and anything from harvesting methods to nothing in particular. He didn’t care, as long as it served its purpose to drive the UK government demented and deny the passage of legislation.

Biggar was a latecomer to active democracy: starting as a town councillor before taking a seat in the House of Commons in 1874 as a Home Rule League and later Irish Parliamentary Party MP for Cavan. Two years earlier he’d led Belfast’s first nationalist parade, calling for the release of Fenian prisoners from English jails.

It was said, in generosity, that Joe lacked physical presence, or that he was “in bodily frame defective,” to quote his good friend T. M. Healy (more anon). His detractors didn’t put a tooth in it, describing him as “a diminutive hunchback.”

It was a cruel and ignorant characterisation. His businessman/banker father “Big Joe” had been a huge man of 22 stones, but when he was 14, Joe jnr was thrown from a pony and his injuries left him with stunted growth and curvature of the spine.

Still, with political correctness still unheard of, not long after he entered parliament Biggar fell foul of Tory prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, who, in a whispered conversation, branded him “the leprechaun”. It stuck.

However, Joe wasn’t in Westminster to make friends. He saw imperial parliament as an enemy fort whose weaponry had inflicted disaster in Ireland. And so he decided to use its own procedures to hold the home of British conservatism in “a state of siege.”

He did this by effecting an ever-more-aggressive form of obstructionism called “filibustering.” This involved giving impossibly long speeches to delay the passage of Irish coercion acts and generally derail the business of the house; thereby forcing the ruling parties to negotiate with nationalists. His advice to colleagues was simple and two-fold: “Never talk unless in Government time” and “Never resign anything, get expelled.”

And so Joe would arrive into the chamber armed to the teeth with books and papers from which he would quote liberally and at length, spraying his words forth in a harsh Ulster rasp, his eyes penetrating the chamber intensely as others nodded off around him.

His Commons cohort, the pioneering journalist and publisher T. P. O’Connor, said that while Biggar, with his “grating” accent, “was one of the most inarticulate of men”, he “had nerves of steel — a courage that did not know the meaning of fear, and that remained calm in the midst of a cyclone of repugnance, hatred, and menace…”

In one instance Joe talked for half an hour on the subject of threshing machines so as to assail and defeat a harvesting bill. Of that particular act of daring, the supportive “Freeman’s Journal” newspaper observed: “Once or twice it seemed as though he had exhausted every possible branch of his subject… but no, Biggar brought out ‘the old flail’. It was a moment of inspiration. Who could not talk for fifteen minutes on [that]” — the prospect greeted by “a groan of mortal anguish” from the government benches.

Another time, three hours into what proved to be a four-hour speech on the Irish Peace Preservation Bill, and with English and Scotch MPs losing the will to live, the chair tried to cut him short: intervening to say that Joe’s weak and husky voice was becoming inaudible, in contravention of a rule that contributions had to be clear to the ear. With that, Joe picked up his pile of papers and glass of water and moved seats to within a yard of the chair, before uttering the dreaded words —

“As you have not heard me, Mr Speaker, perhaps I had better begin all over again.”

As one profile put it, “Probably no member with less qualifications for public speaking ever occupied so much of the time of the House of Commons. None practised parliamentary obstruction more successfully. With a shrill voice and an ugly presence, he had no pretensions to education. But he had great shrewdness, unbounded courage, and a certain rough humour.”

Such was his neck that Biggar once succeeded in having visitors, including the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) ejected from the public gallery during a horse-breeding debate, complaining “I espy strangers!” Though party leader Isaac Butt greeted Joe’s outburst with horror (as he did all his provocative ramblings), it forced the Royal party to withdraw lest its presence be seen to cause undue influence over proceedings.

Though Joe sympathised with Fenianism, he felt a pure reliance on physical force against Britain to be unrealistic. He joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood and was promoted to a senior level before being expelled for being too hung up on his peculiar art of “conversation politics”.

Having entered the British parliament a year after Biggar, but seeing immense value in his diversionary tactics, Home Rule League leader Charles Stewart Parnell greatly valued Joe as an ally. Indeed, his honesty and good nature was admired by most nationalists, who, at party meetings, toasted “the health of Mr Biggar”, the “Irish of the Irish” — and he was sneakingly regarded by his British foes.

In 1880, as violence broke out in the Land War, Biggar, along with his fellow executive members of the Irish National Land League (Joe being its founding treasurer a year earlier) was charged with conspiracy to prevent the payment of rent. He temporarily fled to Paris to escape arrest. They were subsequently acquitted and the Land League surged in strength.

The Antrim man had connections in Waterford and Harry D. Fisher recalled seeing his father, Joseph, then owner-editor of The Munster Express (and a strong advocate for forcing landlords to sell up and leave) discussing a draft Land Bill with Biggar and Parnell at the newspaper’s office on The Quay. These terms and conditions were the basis of the Land Acts subsequently introduced in Ireland to allow peasant or tenant ownership of land.

But his valour and candour could get Biggar in bother. In late 1882 he was served with a summons while visiting relations in Butlerstown. It arose from a speech he’d delivered to a large assembly at Waterford Town Hall, purportedly for the purposes of forming a “national and literary club.”

He was accused of “maliciously contriving to disturb the public peace and raise discontent and disaffection among the Queen’s subjects, and to bring the Government of the country and the administration of justice … into hatred and contempt.”

Biggar appeared before magistrates the following month to answer the charge, which held in prospect a prosecution for sedition against the Crown, “a heinous misdemeanor” punishable by fine and imprisonment. Here was a member of the legislature prevailing thoughts of unrest upon impressionable people, the accusation went.

For the hearing, the court was crowded with lay people, politicians and clergy men. All of 14 press reporters were counted. One of them, Jacob Heatley of the Waterford Standard was asked to give testimony, having been present and taken notes of Biggar’s bombastic denouncement of hangings by the Whig Government based on illegal evidence. The prosecution case was sent forward but, in the event, Joe wasn’t tried.

Bail money

Among those who put up bail was Samuel Ferguson, a relative and property/business partner, who was also a like-minded nationalist from Belfast. Ferguson had carried out large-scale restorations at his southern base, Butlerstown Castle, from the 1860s onwards. An attached house had been built and the castle re-roofed by the previous owner, Robert Backas of Waterford — who had secured a lease, forever, from the Sherlock family. Backas was also a relative of Ferguson’s but sold him the property when he moved his family to the Kilkenny side of the Suir.

The Trinity-educated Ferguson was a multi-tasker — an acclaimed poet, barrister, antiquarian, artist and public servant. As a commentator, he was bitter about the mismanagement of the Irish potato famine, and expressed his feelings in print. As a leading member of the Home Government Association, he regularly held pro-nationalist meetings at his Butlerstown abode.

His Dublin-born wife, who became Lady Ferguson when he was knighted in 1878, was also a writer and publisher. Born Mary Guinness, she was a great-great-niece of Arthur, the flagship brewery founder. On Samuel’s death in Howth in 1885, even though Mary lived another nine years (the couple having had no children), Butlerstown Castle and a hundred acres of adjoining lands were left to Biggar, who assumed it as his would-be bachelor residence in the spring of 1887.

Not that the inheritor intended retiring to the lap of luxury. Joe remained active in Westminster, literally until his dying day. Changes in procedures a couple of years earlier led him to lead a quieter life politically-speaking, much to his opponents’ relief. He gradually became quite the cross-party favourite.

In May 1889, appearing before the Times Commission investigating allegations against Parnell & co., Joe gave a mere 15-minute address to the court in which he frankly avowed he was not only a Fenian but had been a member of the Supreme Council of the I.R.B..

It was to be among his last high-profile pronouncements. Since his adolescent accident, his health had never been robust and in February 1890, at age 62, he succumbed to heart disease during his sleep at Clapham Common, London. Just seven hours before, beyond midnight, he’d been on teller duty to ensure a Parnell amendment was passed.

Biggar was buried in the family plot at Carnmoney after “the most democratic and popular funeral that was ever witnessed in Belfast” up to that point. Parnell, with whom he had a genuinely deep and abiding friendship, was among the chief mourners. He described Biggar as “my first colleague, and at one time my only colleague.” He regretted his loyal lieutenant hadn’t lived another few years to see “the triumph of the cause for which he fought so valiantly.”

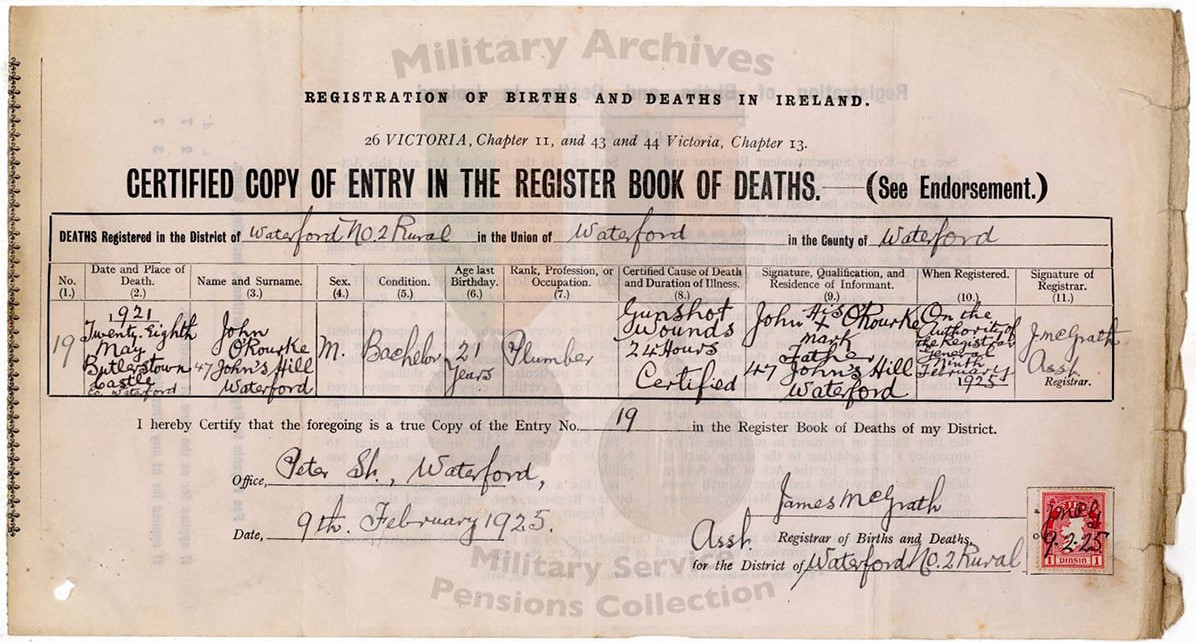

Those were fateful words as, suffering from kidney disease and pneumonia, Parnell passed away, aged 45, in October the following year, and not long after that, another staunch Parnellite, Richard Power of Pembrokestown House, MP for Waterford and Irish Party Whip, died suddenly at 40.

His Will

Biggar left this world a very wealthy man, with a personal estate worth over £37,000. His assets included Butlerstown Castle. In his memoirs, his close friend Tim Healy, the former MP and future first Free State governor, recalled how he spent Joe’s last three summers with him in Butlerstown.

His host’s most enduring trait, he said, was his sheer inability to tell a lie. Healy cited how a former gardener there, whom Biggar had dismissed, had approached his guest to complain about a character reference Joe had given. It read: John Doyle can grow a good crop of vegetables; also a good crop of weeds. J.C. Biggar.

While he acknowledged that Joe “examined his farthings rigorously,” he was bountiful to a fault for deserving causes. However, this didn’t extend, despite claims to the contrary in the press, to leaving the Castle to Healy. The two men had been Parnell’s closest allies, so it might have been no surprise if he had, minded to continue its role as an MPs’ getaway.

However, the Freeman’s Journal of 19 April 1890 carried a piece headed: JOE BIGGAR’S BEQUESTS. THE FACTS OF THE CASE. It stated that the story of Biggar having bequeathed Butlerstown Castle to Healy (as reported in the Dublin Freeman on March 8) “is not true. The Castle is to go for the use of the priest or prelate officiating at Butlerstown, and will form a pleasant adjunct to their presbytery.”

The Journal maintained that Biggar “very rarely stayed at the mansion, which was a year or two ago bequeathed to him by an admiring connection. He used it as a sort of sensatorium for the Parliamentary Party, of which he was a distinguished member. If any member was ill or, being overworked, and needed a rest, Mr. Biggar gave him the key of Butlerstown Castle, and begged him to go there and make himself at home. Last summer Mr. Healy was a resident there for some weeks, a circumstance which has probably given rise to the rumour alluded to.”

Healy insisted that Biggar didn’t leave him any money. Learning his original intentions to do so per one of the earlier editions of his will, Tim said he begged him to dispose of it elsewhere. Joe did leave £200 to Healy’s son, to whom he was godfather.

The bulk of Biggar’s fortune was held in trust for his own natural son, also called Joseph (actual first name Francis, whose mother was a Mary Paulina O’Connor) — provided he be admitted as a solicitor. The son, having made an unsuccessful effort during his father’s lifetime to pass his legal exams, duly qualified later on. More than that, having changed career, he went on to become a serious archaeologist and student of Ulster history, tirelessly promoting all aspects of Irish culture, including folklore and folk music. He was friendly with Roger Casement and Douglas Hyde and a champion of the Gaelic League. Young Joseph died in 1926, aged 63.

Relatively minor legacies were left by his father to a daughter, Margaret, in France (which might explain why a Miss Hyland in Paris had successfully taken a legal action against Biggar for “Breach of Promise of Marriage”), his two sisters, other relatives, servants, and charities. £3,000 was split between three religious orders and institutions.

The estate was, however, subject to certain complicated contingencies as to the real and personal estate to which he was entitled under the will of the late Samuel Ferguson, with the Butlerstown property stated to be “subject to the life interest of Mr. Thomas Gillis” (a cousin of Joseph’s) from Pau, France, who had holidayed there. Thus, the Castle would only pass on to Biggar’s son and namesake after Gillis’s death. (In Kilmeaden Churchyard, there is a monument to Samuel Ferguson “erected by Thomas Gillis and Joseph Gillis Biggar”.)

Pending resolution of this, Biggar’s own will — with the notice of charitable bequests recording the executors as Patrick Joseph Power of Newtown House, Tramore and Richard Power of Tramore House — devised Butlerstown Castle and an adjoining estate of about 150 acres to the Catholic Bishop of Waterford “for the time being” as a residence for the priests officiating in the parish, and their use of the lands, subject to specific payments to three religious-run institutions.

It was a pointed gesture. A year after he was elected to Westminster, Joe had converted to Catholicism in solidarity with Irish nationalism. His Presbyterian parents weren’t best pleased. A cutting of the newspaper announcement was mailed to Biggar by his old man, with an incredulous note underneath asking, “Dear Joseph — Is this true?” His son posted it back with an even shorter scrawled reply: “Dear Father — It is”.

They never met nor spoke again.

Post Comment