Curious George

Jamie O’Keeffe traces how long it took to get to the root of the truth in the Tooth affair, and the gaps in a fanciful story that caused a peerage scandal on both sides of the Irish Sea

“I am the son and heir

Of nothing in particular.”‘How Soon Is Now’ – The Smiths

WHILE the First World War raged and this country was racked by bitter civil upheaval, Anglo-Irish interest was piqued on both sides of the water by the curious case of a humble gardener who claimed to be Waterford royalty.

When it emerged that an Englishman was asserting himself as the lawful eldest son of the fifth Marquess of Waterford, it caused a sensation in high-society and media circles.

The story’s origins were tragic. Florence Grosvenor, first wife of Lord Waterford, John Henry de la Poer Beresford, gave birth to a stillborn child at their home in London on 27th March 1873. A few days later, she also died at Chesham Place, Belgravia.

The Marchioness’s remains were transported to Waterford and buried in the family vault on the estate. Her baby boy’s remains were exhumed and returned with her. A tombstone was erected at Clonagam Church bearing an effigy depicting a mother recumbent with a child in her arms. Its inscription refers to them both.

It transpired that early the previous year, the then-Lady Waterford had stayed in a Franciscan Convent on Portobello Road in London as she contemplated a change of religion to Roman Catholicism; something said to have caused no little concern within the Beresford family.

While there, she learned from a maid companion that her cook Sarah Jones’ sister, Georgina Tooth — who had previously been a servant of the then-Mrs. John Vivian — had given birth to a baby boy in nearby Holborn Union Workhouse but died a short time later.

Affected by the child’s plight, Florence arranged for the infant, nominally named John, to be taken from the workhouse and christened George, after his mother. She also made provision for him to be looked after and educated by a Mrs. Duncan, a nurse known to the family. Lady Waterford’s husband would continue this bequest after her passing.

In the years that followed, the boy George would sometimes visit the Marquis’s English home at Piccadilly, brought by his foster mother, and later her daughter. But support payments, made on the 8th of every month, stopped when the lad entered manhood. “Toothy”, as he was known during his Chelsea schooldays, wrote to Lord Waterford to complain. The Marquis replied that he had been given a start in life but needed to make his own way as an adult.

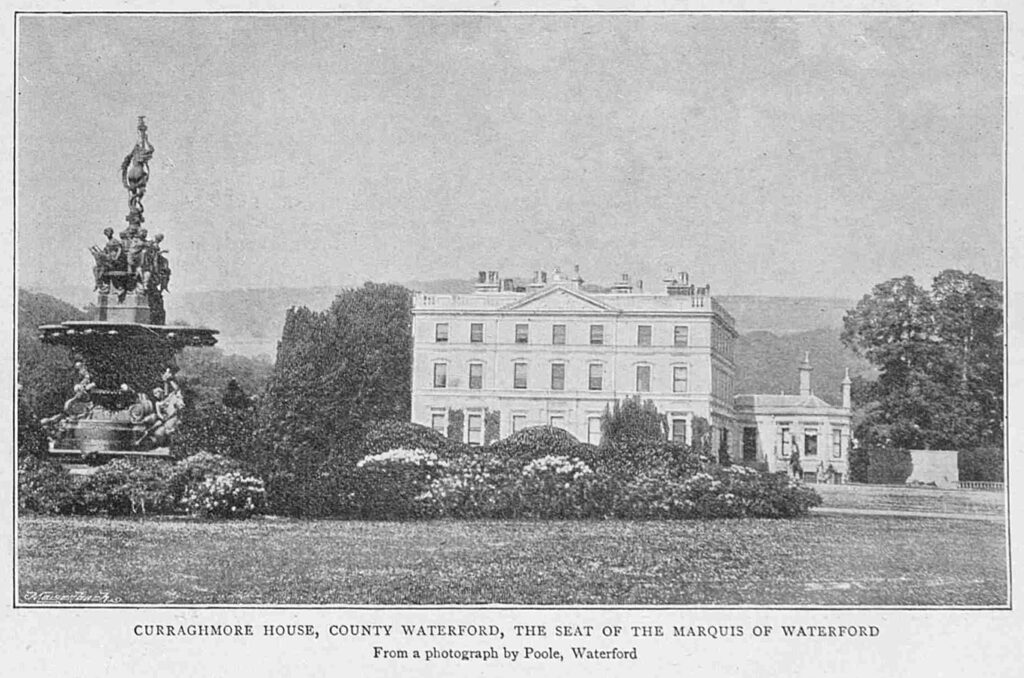

Having been wheelchair-bound after a hunting accident some years earlier, in 1895 John Henry Beresford shot himself in his study in Curraghmore, aged 51. It was then that Tooth — by now married and a father of four, struggling to make ends meet — began his peerage quest in earnest, maintaining he was, in fact, the fifth Marquis’s true ‘son and heir’.

Plaguing the deceased Marquis’s brother Charles to have his claim recognised, George insisted he was the rightful inheritor of the family seat, not Henry, the sole son the late John’s second marriage to Lady Blanche Somerset had yielded (whose sisters included the future Lady Susan Dawnay of Whitfield Court).

In July 1905, Tooth wrote to the new Lord Waterford asking for assistance to take his family to the Colonies. “I am willing to sign any document not to trouble your lordship again or any member of the family,” he offered. In late 1911, he penned a further letter: threatening to ‘make his whole case public in a well-known journal’. He wasn’t seeking the entire estate, just ‘an amicable settlement’.

To gain publicity, and to be paid for his silence, Tooth had taken to perambulating about London with sandwich boards declaring himself Curraghmore’s actual next in line. The appearance of a man attired in frock coat and silk hat carrying placards saying “I AM THE SIXTH MARQUIS OF WATERFORD – I DO THIS TO FORWARD MY CASE AND OBTAIN JUSTICE” caused more than a ripple of interest on Fleet Street. Allied to the serial misfortune that dogged the dynasty, it made for a salacious story.

According to George’s self-serving version of events, long before he could possibly remember, he had been secreted as a baby in Lord Waterford’s carriage and pair from the Beresfords’ London abode and put out to nurse with Mrs. Duncan in Fulham, who raised him as George Tooth.

To add a layer of complexity and intrigue, the Waterfords were said to have admitted that a child was sent to the same woman to be brought up. However, they denied it was Lady Florence’s new-born baby but rather the illegitimate child of a staff member, which arrived some months before the dual registry-office and Church of England marriage of John Henry and the ex-Mrs. Vivian in August 1872.

Clandestine lovers, in 1869 they had eloped from Curraghmore to Paris in scandalous circumstances until ‘Florrie’ was chased and divorced by her enraged army-captain husband (attempting suicide by chloroform, she had refused to return to him and their two children). Tooth claimed he was born on 29th March 1873, intimating he may well have been a product of this illicit relationship and thus a persona non grata at birth.

In 1912, he gave an interview to his local paper, the ‘Norwood News’. He alleged that the late John Henry, at a time when he seemed close to death following his hunting accident, had told him to consider themselves father and son.

The plot thick enough to cause a modicum of doubt, and desperately “want of funds”, George decided to legally pursue his sense of entitlement. He took a civil action for slander after Priscilla White, the maid who had apparently told Florence about the workhouse baby and assisted its safe passage, publicly poured scorn on the notion that he was ever a successor to the Marquisate.

She gave evidence that she was in the room with Lady Waterford the night she gave birth to a still-born son and had been handed the dead child. Lord Waterford was there too, greatly distressed, comforted by his brothers.

Before she died, Florence expressed the wish that her baby be buried with her. Mrs. White was also present at the funerals in Curraghmore. The child’s coffin was beside that of Lady Waterford all night, and both were laid to rest together, she vouched.

The case went to the Court of Appeal in March 1914 but was swiftly dismissed — upon which Tooth immediately began sending Mrs. White abusive mail, accusing her of being a liar and involved in “a great conspiracy” against him. Arrested, he was brought before a Police Court on remand for publishing a defamatory libel.

Though the charge sheet stated his name, as given to the constabulary, to be George de la Poer Beresford, prosecuting counsel referred to the accused’s more familiar alias around Wimbledon Common.

Judge John de Grey was told the prisoner had written letters and postcards to Mrs. White, by now the wife of a Lincolnshire banker, alleging she was a “perjurer” and “murderess.” He signed them ‘Sixth Earl of Waterford’. The newspaper’s solicitor said Tooth’s chances of being that were about as great as his “of being the next Emperor of Germany”.

In the 20 years he’d spent claiming to be the late Lord and Lady Waterford’s presumed-deceased child, Tooth had been a brewery worker, then a woodchopper in a Church Army Labour Home, before becoming a jobbing gardener and sometime cowhand. Faraway fields near Portlaw clearly looked greener.

Sent for trial at the Old Bailey, Tooth initially considered a defence of justification but, fearing jail, entered a plea of guilty and apologised. He was bound over to keep the peace for 12 months.

The following year he brought an unsuccessful libel action against the 2-million-selling ‘News of the World’ over its reporting of the case, specifically a headline which read: ‘Lies Nailed Down. Sequel to Gardener’s Claim to Peerage’, and a passage that said his guilty plea meant the plaintiff could no longer support his claim.

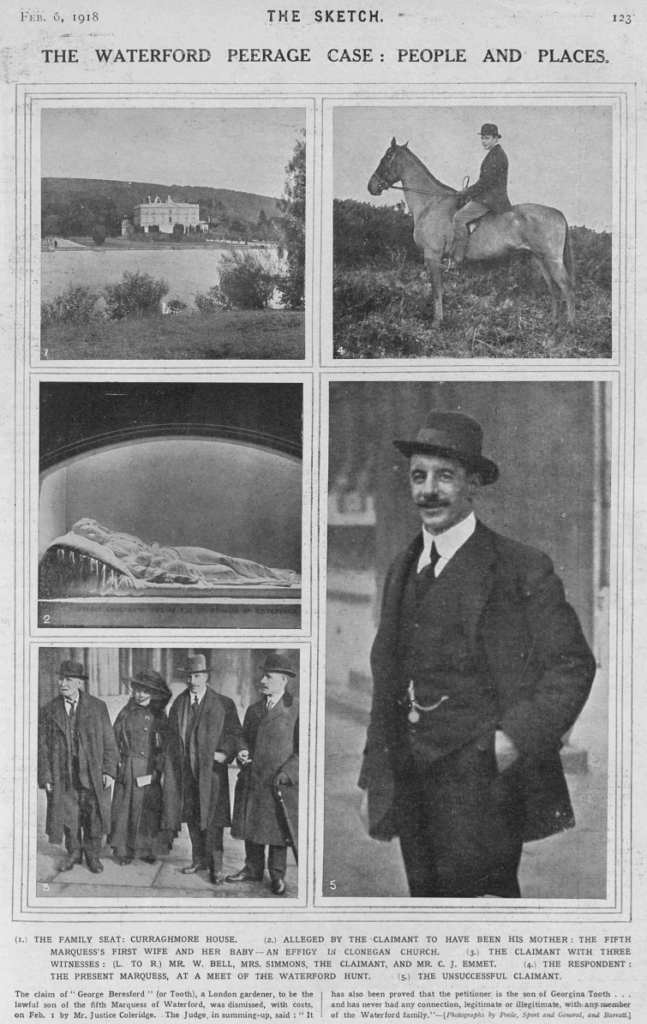

Funded by a mysterious “Mrs C.”, in January 1917 Tooth made an application to have the evidence given by witnesses three years previously published as part of a fresh case; only this time the Beresford family, long the subject of painful “gossip”, were determined to end the innuendo for once and for all.

The hearing lasted several days — poring over wildly conflicting and elaborate accounts — before the verdict was handed down. By any reasonable reckoning, Tooth was not, and could not be, the son of Lord Waterford. The complainant’s version of a plot involving countless parties in two countries covering up a “smuggled babe”, not to mention “a sham burial” and faked memorial tomb, was too outlandish to countenance.

“It is hard to know how he found anyone to support his impudent pretensions,” stated an editorial in the ‘Times’ of London, no less. “Tooth’s case was clumsy, variable, and tenuous … No feebler attempt to obtain a title and estates has ever been recorded.”

Condemning the “female busybody who encouraged him,” the leader read: “The story contained many of the customary ingredients in such litigation – not least a kidnapped infant.” It noted that at one stage Tooth had even suggested Florence had given birth to twins, of whom one was born dead and the other alive.

“No effort was made to show with what motive a young peer, whose dearest hope must have been to have an heir, should have banished and consigned to poverty and obscurity the baby son of a woman whom he had loved with an ardour which outran discretion,” the ‘Times’ exclaimed, saying the truth was that Tooth’s association with the Beresford family had been “purely eleemosynary” (benevolent).

Undaunted, George tried yet again in early 1918, lodging a petition before the Probate Division in London under the Legitimacy Declaration Act, seeking a ruling that he was the rightful heir to a fortune.

The ‘Daily Mirror’ splashed a selection of court photos on its front page. Upper-class magazine ‘The Sketch’ also published pictures of the duelling parties and of the princely prize at stake, majestic Curraghmore estate. Indeed, newspapers throughout England devoted countless column inches to the proceedings. The public couldn’t get enough of this intriguing tale of either impersonation or truth.

However, what proved to be Tooth’s last throw of the dice failed. The legal team for the Trustees of the then-infant Lord Waterford implored that “not a tittle of evidence” had been produced to substantiate the petitioner’s “libellous and infamous” charges.

With Mrs. Duncan having died, his main witness was a Mr. William Bell from Leeds, a moulder who was working in Curraghmore at the time Florence was brought there for burial. He claimed he had looked into the vault during the funeral and never saw a child’s coffin. Under cross-examination, he failed to notice the imposing memorial at Clonagam and had not seen nor heard about the death notice in the press. Bill Bell’s account simply didn’t ring true.

A mountain of evidence contradicting Tooth’s tale was produced, including undertakers’ sworn statements, and entries from the Workhouse showing the admission of Georgina Tooth, the birth of her baby ‘John’ on January 25, 1872, his mother’s death, and his discharge at three weeks old to ‘Vivian, Upper Brook Street, Governor Square.’

Having presented his client’s case in an insinuating light — Why had Lady and Lord Waterford taken such an inordinate interest in the welfare of their cook’s sister’s baby boy? Why had a common gardener gone to the ends of the legal earth to establish his birthright? — by closing arguments, the near-silent solicitor for the petitioner had essentially conceded the case.

Lawyers for the Beresford family rejected Tooth’s whole narrative as preposterous and appallingly unappreciative of the Marchioness’s act of kindness. This generosity was faithfully upheld by her husband, who had married again and by this time passed his title to two descendants, namely his son Henry (who accidentally drowned in the River Clodiagh in 1911 aged 36, coinciding with Tooth’s initial legal offensive) and then Henry’s son John (who was only 17 when the final case went to court and would die in an apparent accident in the gunroom at Curraghmore in 1934).

In summing up, Mr. Justice Coleridge said, “in the face of all these facts … I should be credulous indeed if I were to adopt so incredible a story … that the child was born alive and survived, that it was smuggled out of the house without the knowledge of the servants, and that some dead child was smuggled in” in its place.

He said it had been “conclusively proved” by way of the doctor’s death certificate and other evidence, including the making of the coffin, public announcements, a burial at Brompton and exhumation before being re-interred, “that Lady Waterford had a still-born child on March 29, 1873, and that she and her little one are sleeping together at Curraghmore.”

The learned Judge added: “It has also been proved that the petitioner is the son of Georgina Tooth, born in Holborn Workhouse on January 25, 1872, and has never had any connection, legitimate or illegitimate, with any member of the Waterford family.”

He did not want to judge the claimant harshly as at one time he may have believed there to be some substance to “a story that lends itself to romance”. After everything was said and done, however, “all I can say of him is that he is a man who has proved himself incapable of the feeling of gratitude.”

The finding was definitive. At 46, by biting the hand that fed him, George Tooth’s attempts to make it from the Workhouse and back gardens to the Big House and its vast estate, had ruined whatever good name he once had — a name he was given in his poor mother’s memory.

Post Comment