Memorial recalls The Fallen of First World War

Written on the centenary of the 1918 Armistice, Jamie O’Keeffe reflects on the enduring legacy of loss wrought by the Great War throughout Waterford.

TREATED for too long like one of Ireland’s guilty secrets, the 1,100 men and women from Waterford city and county who lost their lives during the Great War were barely and rarely spoken of. The context in which they went in the first place was neither explained nor understood. Not only were half of them denied the dignity of a funeral, but in a great many more cases their very existence had been virtually hidden from view for nearly a hundred years.

In hindsight, the extent to which the city and county was affected beggars belief. Eleven hundred lost souls. No parish escaped the carnage. Over 200,000 Irish men fought in the First World War and some historians estimate that just under 30,000 of them died.

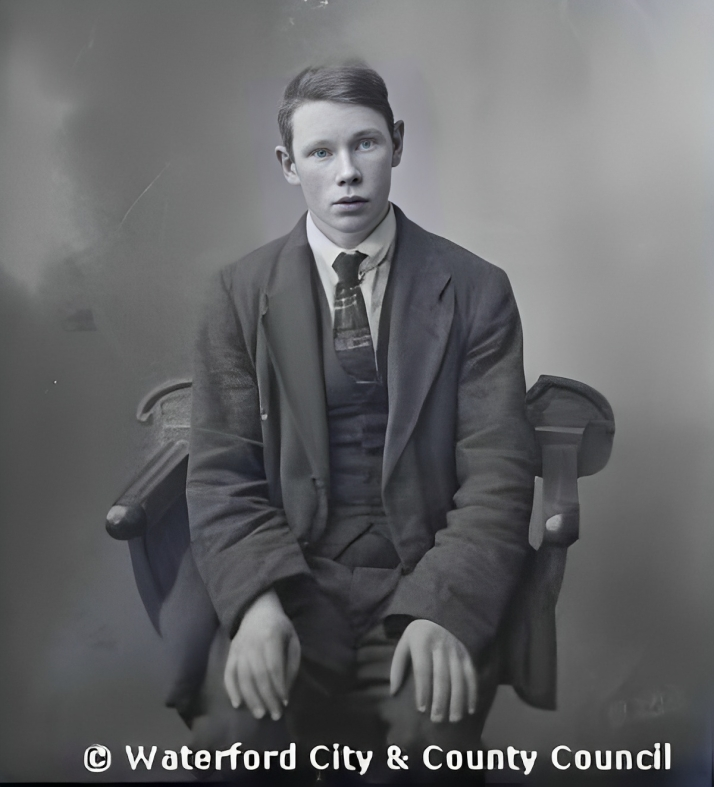

Waterford was a major recruiting ground for the Munster Fusiliers and the Royal Irish Regiment, as well as the Royal Navy. The reasons why these mostly young men and women signed up, willingly sent to fight in far-flung places, were varied. More often than not they went purely out of a sense of duty, or adventure, or as a source of employment. Sometimes all of these factors applied. Others were innocent civilians.

And yet it was if these people — family members, work colleagues, team-mates — just disappeared from public memory. It didn’t sit easily with many people with a sense of history and decency, not least the relatives of those who died. There were also the multiples more injured and traumatised by the experience, most of whom felt it was something they couldn’t talk about, that what they sacrificed was somehow a cause for shame.

Rather than being shunned, these individuals, the local embodiment of an awful global calamity, deserved a measure of honour and closure. Allowing these citizens, who came from our communities, to remain in obscurity, was wrong.

It transpired that almost half of the 1,100 or so people who were ultimately named on what became the Waterford Memorial in Dungarvan have no known grave. Many of their families had never seen their names commemorated anywhere. That was the memorial committee’s motivation, nothing more: to provide a special place of remembrance on home soil. It was long overdue.

Whatever the historical debate, the human-interest stories behind the monument’s long list of inscriptions are countless; each capturing the tragic consequences of war. For example, four of six Collins brothers from Waterford City who joined the Allied effort were killed in action. To this day, they, like hundreds of others named on the wall, lie in unmarked graves.

Jim Shine from Abbeyside, whose three half-brothers — sons from his father’s first marriage — died in Flanders fields. Jim mentioned how so many Waterford men were remembered by people in Ypres and other towns and villages in Belgium. Our war dead were honoured thanks to the kindness of strangers; but not in the place they hailed from.

As well as those who died on the front, significant numbers from Waterford also lost their lives at sea. Most of them were merchant seamen; typically fathers with young families.

Former County Librarian Donald Brady delivered a lecture for the County Museum Society on the centenary of the 1918 torpedoing of the RMS Leinster in the Irish Sea, causing catastrophic loss of life, including seven victims from Waterford. Perhaps the greatest single disaster in the Irish experience of the First World War, yet scarcely acknowledged, it occurred, poignantly, just a month before hostilities were ceased that November.

The perspective of those involved in the war at first hand is both informative and paramount. Brigadier-General Robert Gelston Atkins came to Pouldrew House, Kilmeaden in 1931 and lived there for three decades. A doctor by profession and well-liked in the community, the Cork native had received the Distinguished Medal of Service for his leading role with the Royal Army Medical Corps ambulance fleet in WWI.

After witnessing the very worst of the conflict, he and his first wife Ena (née Hudson, from Helvick) then lost their only son, Bob Jr, in WWII. Dr Atkins was president of the British Legion branch in Waterford and on the 50th anniversary of the Armistice, at a time when many Irish veterans were still hospitalised as a result of both the 1914-’18 war and its successor, and the bereaved were living daily with its aftermath.

“The Irish who went out to take part in these wars knew very well the risk of death or wounds,” he said. “Yet they went in a great effort to retain freedom of the world… They knew, too, that the generations that would come after would benefit more than their own.”

While people have different takes on the history, and the arguments about the politics of that era will go on for years, it’s important to reflect on the fallen as individuals first and foremost; ordinary people who went to serve for what they considered to be a just cause.

In considering the type of memorial to construct, committee chair John Deasy was familiar with the Vietnam Wall in Washington, D.C., having been based there in the nineties. "I felt something similar, albeit on a much smaller scale, would be appropriate." And so Dungarvan monumental sculptor David Kiely went to work on the concept: culminating in a 50 foot-long black granite reminder of the ravages of war, painstakingly inscribed with identities and the places they came from. The sheer scale of the memorial and the individual losses it represents is striking — the impact the war had on Waterford really hits home.

Post Comment