Waterford railed against Tramore line closure

Why Todd tore up the Tramore train tracks

“This was a railway service which was supposed to be losing £3,000. Never did they use any vision. They sent the efficiency experts, the dictators. When the old ‘dodderers’ were running the railway, they were able to have £30,000 in their reserves. That was when they were using an old line and an old-fashioned brass engine. But in those days it used to be baskets of coal, shovelled in by what the experts called an inefficient fireman. The Taoiseach said the Tramore railway line was not economically important – the Dublin mentality. The only efficiency CIÉ showed was in the tearing up of the tracks when, on a wet day, the workmen came along, minutes after the close down order, and tore down the bridge and then began to tear up the line. It was done with the most indecent haste I ever saw. Todd Andrews was able to do that in a few hours. They had their minds made up that they were going to wreck this railway – an old Lemass policy – at all costs. They’d drag the people out of the trains, if they could.”

Waterford Fine Gael TD, Teddy Lynch

While sentiment never paid any bills, to many people’s minds, the abandonment of the Waterford–Tramore Railway line is still regarded as one of the most short-sighted decisions taken as part of CIE’s controversial closure programme back in the early 1960s.

Imposed in the name of “progress”, forcing traffic onto choked-up roads, it remains a dubious milestone more than half a century on. Politically, Fianna Fáil paid a price in Waterford in the October 1961 general election, with Billy Kenneally – who’d topped the poll four years earlier – deposed as a TD, albeit after the constituency was reduced to a 3-seater.

Minister for Transport and Power and future President of Ireland, Erskine Childers, and CIÉ chairman, Dr. Todd Andrews (an arrogant dictator or brilliant decision-maker, depending on your perspective) both became hugely unpopular. A veteran of the War of Independence and a founder member of Fianna Fail, Christopher Stephen Andrews (he acquired his nickname from Alonzo Todd, a comic book character with whom he bore a remarkable resemblance) had been a spectacularly successful managing director of Bord na Móna, when Seán Lemass appointed him chairman of Córas lompair Eireann in September 1958.

At the time, the company employed 20,000 workers, and had 2,500 miles of railway as well as 7,000 lorries, 1,200 buses, 200 horses, and 450 miles of canal. However, it was losing millions of pounds annually. Andrews immediately passed the Transport Act, requiring the company to pay its way within five years. He pruned the railway network drastically, reorganised the management, and by 1961 had brought CIÉ to within £250,000 of breaking even.

But it was a fiscal policy which came at a price. Before Andrews wielded his knife, Ireland still maintained the bulk of the great railway system it had inherited on Independence, though a number of the peripheral western lines and central branches had already closed.

However, his son, former Fianna Fáil minister David Andrews, has said: “My father was a strong leader and a loyal leader. And that leadership was driven by a strong sense of direction. He knew what he wanted [but it] was always in the interest of people other than himself.” Others saw him in a less glowing light. Indeed, so intense were the passions he fuelled that an effigy of him was burned in West Cork to the strains of the Soviet national anthem.

In the beginning

Built through fundraising by Waterford businessmen, after a special Act of Parliament was passed in Westminster, the Waterford–Tramore railway cost roughly £5,500 per mile to construct. The first sod was turned on February 10th, 1853 and the short, self-contained line was completed, amazingly, by contractors William Dargan & company on September 2nd that year.

The first 15-minute train between Waterford and Tramore’s respective Railway Squares ran on September 15th. Some 10,000 people watched along the 7.25-mile route, marvelling at the enormous locomotive (the “Iron Horse”) as it whistled in salute.

An enlightened promotional push by the directors, offering various ‘freebies’ (particularly for persons moving out to Tramore to live), ensured the service was an instant success. Indeed, such was the crush for the 7.30pm train in the first week that the police had to be called in to prevent a riot.

In 1925, having been a relatively prosperous concern while independently owned, the line was taken over by the Great Southern Railway and in 1930 had to compete with a new rival means of transport, the ‘Nomad Bus’ service, launched by Waterford businessmen; it was discontinued when the train company slashed its fares and, via a Government Act, subsequently bought out the bus firm. During the thirties, special trains were organised to bring thousands of children from poor families to the seaside once a year.

The introduction of cheap fares in 1952 saw a huge surge in business, with 14 trains daily in both directions, queues of passengers and packed carriages. The half-hour service operated throughout the summer, with trains teeming with tourists, as amusement arcade owners waited eagerly for the sound of a steam engine on the home straight.

The 0720 return on Sunday evenings (aka “the drunkards’ train”) carried up to 2,000 passengers, many of them “well on”. As you’d expect, the August racing festival was a hugely busy time, with 3,680 train passengers carried on Sunday the 15th, 1959. However, despite the dawn of the diesel engine in late 1954, the good times didn’t last. Indeed, while steam could carry up to 2,000 passengers in 20 minutes, the supposedly superior diesel version was only able to pull 600 in 15, leaving lines of disappointed customers on the platform.

With the railcars thus unable to cope with the heavy traffic – and replacing the rolling stock and upgrading the line and facilities cost-prohibitive – Waterford Corporation responded by putting on extra buses at peak periods. Also, the motor car was becoming more affordable, so much so that on Sunday afternoons the Prom would be packed with automobiles right down towards the sandhills. Still, the resultant traffic tailbacks on so-called gala Sundays made the train a vital alternative. However, the end of the line was near.

Viability questioned

In the early fifties, CIÉ (formerly Great Southern Railways) took over its operation and, citing rising costs and poor public support – including that from merchants, when it was never a goods train – served a clear warning that the line’s future viability was in doubt. In the winter of 1955, the booking offices at Waterford and Tramore were closed, only opening during the summer and other peak times.

The service survived until I960 when Dr. Andrews, cutting a swathe of destruction through rail routes across the land, announced its imminent closure – ignoring an eleventh-hour deputation from Waterford after motions of protest were passed by both the Corporation and County Council.

The tough-talking Fine Gael deputy, Thaddeus “Teddy” Lynch – a two-time Mayor of Waterford – led the condemnation of Government/CIÉ policy saying the line had been “priced out of existence… Waterford men were pioneer promoters of railway building in this country,” he said.

However, hecklers jeered that he was merely “letting off steam” and “going off the rails”, while themselves insisting that rail travel was outmoded and simply unable to pay its way. (He wasn’t helped by suggestions from other southeast TDs that people coming in from Tipperary and Kilkenny would prefer to get straight on the Tramore bus on the north side of the Suir than having to traipse 2 miles across the city to the train terminus. Buses also offered more stopping points.)

In a last-ditch bid to rescue the railway – or rather call Fianna Fáil’s bluff – Lynch and Dungarvan-based Labour TD Tom Kyne sent an urgent telegram to Andrews’ office asking for a stay of execution, stating that both local authorities had each agreed to put up £1,000 each towards defraying the line’s loss.

They also raised the issue of flooding on the main Waterford–Tramore road and its impact on the proposed replacement bus services – not to mention the cost to Waterford ratepayers of upgrading/maintaining the route to accommodate the increased double-decker traffic, which local engineers estimated at £100,000 and £15,000 p.a. respectively.

Waterford’s Chamber of Commerce and Council of Trade Unions joined the chorus of condemnation. J. J. Walsh, proprietor of The Munster Express, wrote editorials saying the decision would cause road congestion and traffic accidents. He led a deputation to Dublin to lobby Andrews to no avail. The Minister, Erskine Childers – described by Deputy Lynch as “the great pooh-pooher himself” – merely said: “When a railway service ceases, agitation is inevitable”; adding that Waterford still had some 200 miles of railways remaining.

In response, Lynch urged those with cars travelling to and from Tramore to give people lifts “and leave those CIÉ buses standing there.” However, with the substitute bus service dearer than the train was – the train had brought people for 1/ 9 return, whereas the bus cost 2/8d; a fare which mothers with big families couldn’t afford – the people of Tramore established a contract bus service of their own, taking a few thousand pounds a year out of CIÉ coffers.

Indecent haste

While there were just three direct redundancies involved in the Tramore closure, the effect was manifold. The biggest mistake in most people’s eyes was not just shutting the lines, but tearing them up. Indeed, the expediency with which they went about it was startling. Within a few months of the last train journey, the Tramore track was dismantled with what Deputy Lynch decried in the Dáil as “indecent haste.”

He added: “The only time I saw real efficiency in CIÉ was at the time of the destruction of the Tramore railway. The order to close it came into operation at 2 o’clock on a Saturday and in the teeming rain, in the most malicious, vindictive and devilish manner, men were paid extra money to pound down this Metal Bridge and make sure this railway line was broken up so that there could be no agitation” (despite Seán Lemass having previously given, as Minister for Industry and Commerce, “a solemn undertaking that no railway line would be taken up without full consultation with the local people”).

It was, Lynch said, “a shameful and blackguardly act.” For years after, he in particular refused to let the matter rest, pressing the Minister as to how many more passengers CIÉ had carried by bus than train between Waterford and Tramore since the line was shut. Childers refused to state specifics, merely saying that the figures showed “only a very small increase.” In fact, particulars for the calendar year 1961 showed 403,836 passengers used CIÉ’s Waterford/Tramore buses, compared with 424,000 carried by the rail service in the year ended March 31st, 1959.

However, said the Minister, when the services arranged privately were added, “the total number of people who travelled was 40,000 greater in the period April–October 1961, than in the period April–October, I960.” Moreover, the substitute CIÉ bus service during 1961 produced an operating profit, whereas “the former railway was operating at a loss at the time of closure.”

Final journey

The last train ran from Tramore to the city on December 31st, I960, bringing to an end what was for many people, a way of life. The tracks were lifted in their entirety by May the following year, with the scrap iron about to be all sold off to Czechoslovakia and elsewhere overseas (much of it destined for foreign shores on board Costa Rican ships from Cork) before objections were raised in the Dáil and an Irish firm eventually won the tender. Many of the railway sleepers are still in use as gate posts by local farmers, with the County Council making use of the rest to protect the sandhills from erosion.

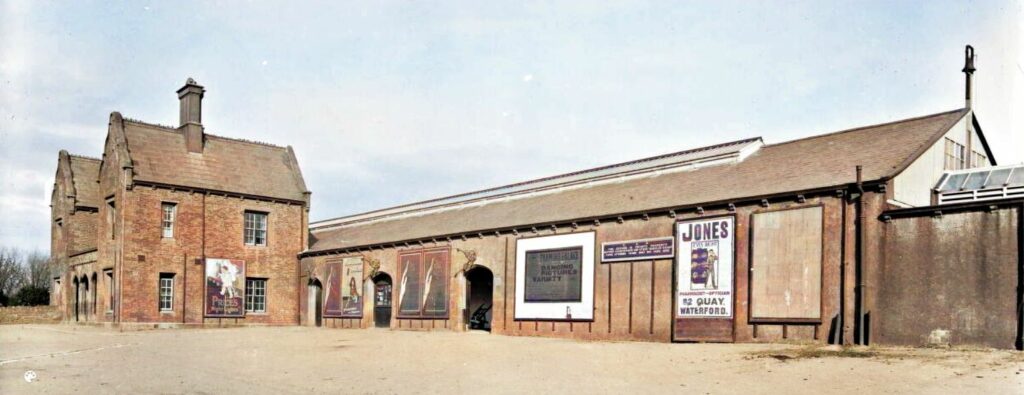

Residents of the Waterford Road alongside the rail line were offered the adjacent strip of land for the nominal sum of £1, with CIE paying £5 towards the legal costs. The ‘Manor Street Station’ in the city was demolished in the mid-sixties (the old railway shed having been knocked in 1954 and the rusting old steam engines scrapped soon after). The main terminus building at the end of Train Hill in Tramore remains in situ and has been earmarked for various developments over the years.

The Waterford & Kilmeaden Heritage Railway project was initially conceived in 1997 as a proposed resurrection of part of the Tramore track. However, those plans were abandoned in favour of a section of the old Dungarvan line along by the River Suir.

Post Comment