Richard captured old Ireland

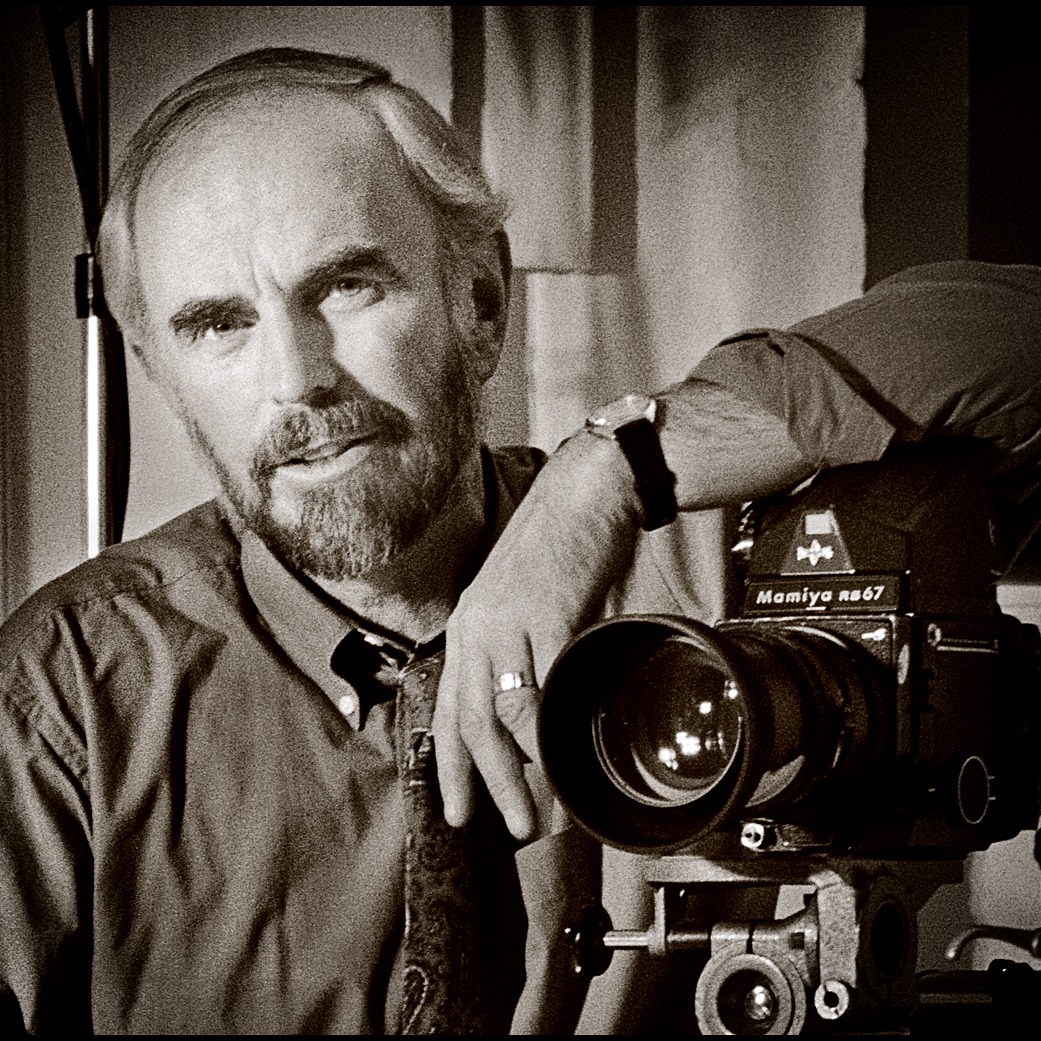

Richard Fitzgerald, one of Ireland’s most influential ‘old world’ photographers, died in England in November 2019.

Son of Ballyduff hurler Michael “Mull” Fitzgerald, who won an All-Ireland junior medal with Waterford in 1931, Richard was born in 1943 in a thatched, whitewashed dwelling in Portlaw. He was just a baby when, that October, his mother Eily (née Ellen Power, whose siblings included William, Killotteran Lodge) died at the tragically young age of 30.

His father, who had been employed in Coolfin Sawmills, emigrated to Scotland and Richard was raised by his aunt and uncle, Mai and Tommy Giles, in their traditional cottage at Blacknock, Kilmeaden. He was always thankful to the family for those formative years, during which he attended Ballyduff National School.

In 1960, Dick, as he was known locally, left on the ferry for England along with another Kilmeaden lad, 22-year-old Thomas Joseph O’Shea, a charismatic personality, singer and comic.

Tommy had been reared by his grandmother Mary-Kate Kearney at the family forge in Gortaclode and worked in the woods at Mount Congreve. The friends went through some very tough times before finding their feet on the bustling, unforgiving streets of London.

For his part, Richard, unable to get into college, fortuitously rented a room in a house owned by professional photographer Cecil Stone, who had a studio and darkroom at home. He taught his lodger about lighting and the secrets of mixing chemicals to tone prints.

Securing employment as a darkroom printer with a Fleet Street press agency, in the mid-sixties Richard got a job as a photographer on a luxury cruise liner. Landing back in London, he struck out on his own as a studio-cum-magazine lensman. Soon actors, models and musicians, including Queen, Paul McCartney, The Who and Marc Bolan were among his celebrity clients.

Richard married Louise Mary Jansen in Surrey in September ’72 (with Tommy, by now a cabaret artist, his best man) and the newly-weds spent some of their honeymoon with the Giles family in Kilmeaden.

He hadn’t set foot back in Ireland till the early seventies, and was “astonished how the old world I knew from my childhood was fast disappearing … It was as if it was stealing away almost unnoticed in the rush of modernisation.”

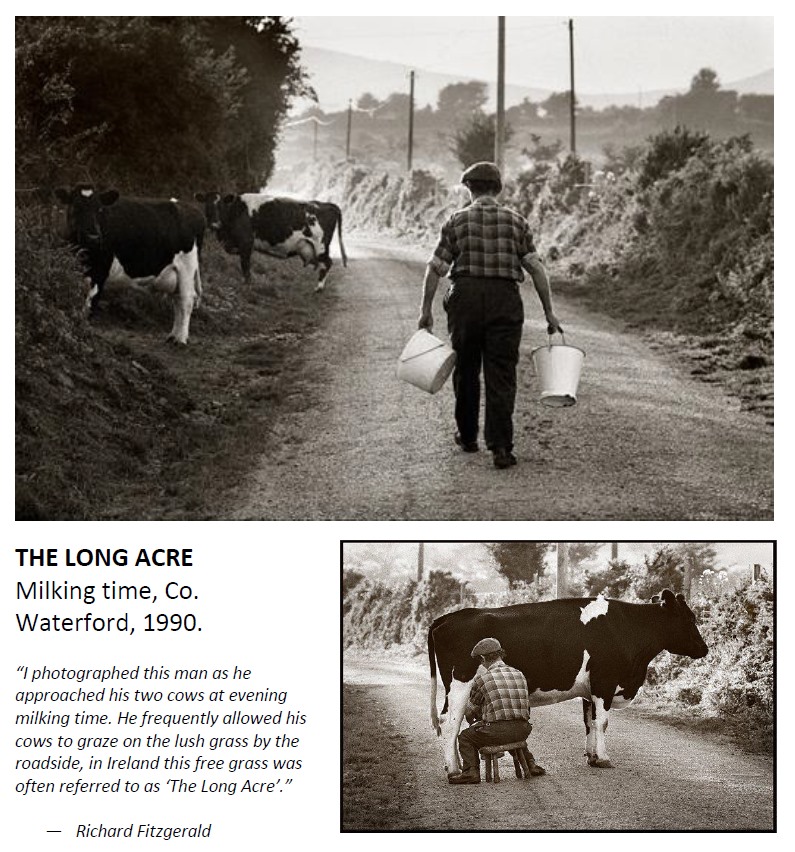

He wanted to capture its essence before it was gone and so his summer holidays doubled as an annual pilgrimage: to frame what remained of the ways and by-ways of the countryside he grew up in. He was particularly drawn to desolate landscapes, dotted with abandoned stone cottages and derelict farmhouses.

As he explained in the mid-’80s, “Neglected houses just go back to the land. Whitewash vanishes with rain. Houses get used for livestock and then fall into ruin. It’s very sad.”

Richard also focused on evocative portraits of hardworking if often-repressed people — like elderly couples whose sons and daughters had long since emigrated, lonely bachelors, and religious spinsters. Though sometimes semi-staged rather than spontaneous, these photographs of weather-worn faces, spartan living conditions, and bleak, barren outposts accurately represented how things were in the not-too-distant past.

His personal cultural-preservation project gave rise to three acclaimed books: beginning with the first instalment of the definitive ‘Vanishing Ireland’ series (above), which had its genesis in an exhibition at Waterford’s Garter Lane Arts Centre in 1987.

‘Ireland: The Parting Glass’ (2004) followed along similar lines, as did last year’s even-moodier Patrick Kavanagh-inspired collection ‘Dark Ireland: Images of a Lost World’.

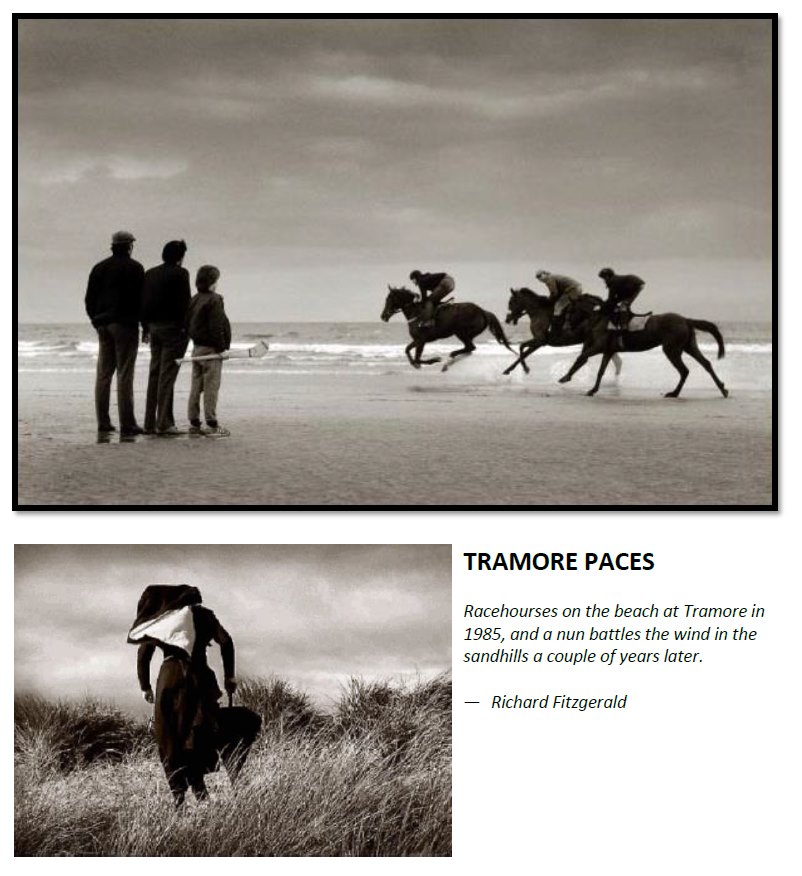

Though he spent a lot of holiday-time in Tramore, to find the kind of raw material he was looking for, Richard typically headed to the west of Ireland and also the back roads, farms and cottages of the Comeragh foothills.

It was there he stumbled upon the characters for an award-winning 2006 documentary called ‘The Brothers,’ which was commissioned by RTÉ television and watched by half-a-million people on first screening. Portraying the lives of two elderly bachelor farmers, Paddy and Nicholas Butler, it was filmed by Richard over a decade, with a dramatic and unexpected twist in the tale.

That he generally shot in stark, sometimes-haunting black and white was no coincidence. “As a young boy trying to make sense of my surroundings, Ireland seemed a very dark bewildering place,” Richard reflected a few years ago.

“Our village didn’t have electricity and the other conveniences one might associate with 1950s life … I remember the local roads as dark and mysterious places, where shadowy figures moved in the twilight … often the sound of horses’ hooves in the distance … homes were dimly lit with the calm flickering flames of candlelight and Tilly lamps … of all the rich colours stored in my memory, black is by far the most prominent and persistent.”

Tinged with melancholy and no little personal loss, Richard Fitzgerald’s fine legacy is an elegy for a time which he, for one, wished had stood still.

Post Comment